The Paper: “A Study of a Section in Kakaako,” between 1933 and 1935

The Writers: M.N. and G.F.

Location in RASRL: Box A-4

The Maps and the Table

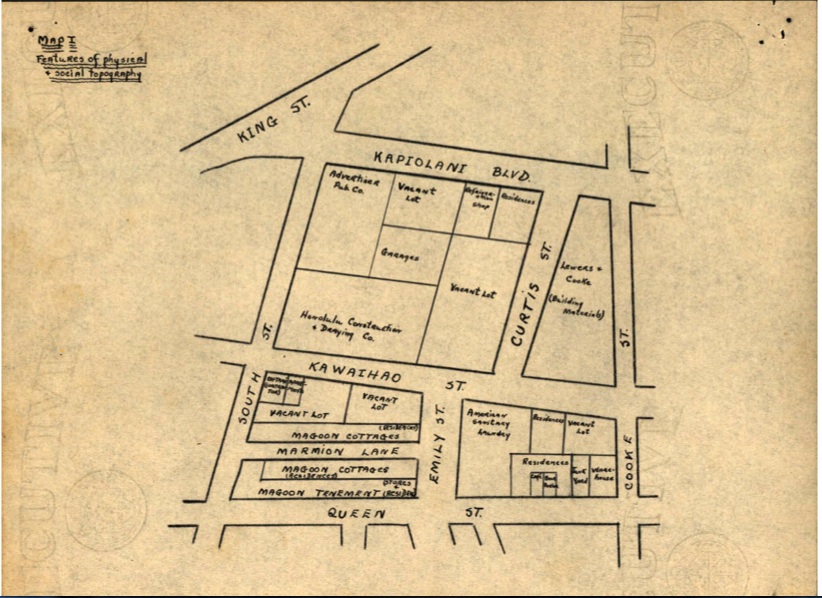

The area is a carefully delineated section of Kaka‘ako with “an intensive study” of the Magoon block and Marmion Lane. A transition zone, this area of Kaka‘ako, near Honolulu’s central business district, is a mixture of working class residences, industrial plants, businesses, and warehouses.

Map I, “features of physical & social topography,” identifies business concerns: on Kapi‘olani are the Advertiser Publishing Co., a refrigeration shop, and Lewers & Cooke. Along Kawaiaha‘o are the Honolulu Construction & Draying (H.C. & D.) Co., Ohtani Contractor, and the American Sanitary Laundry, a Magoon enterprise. Along Queen, on the bottom of the map, are Magoon-owned properties – labeled “cottages” and a “tenement.” Additional residences and small businesses are on the Diamond Head end of Queen.

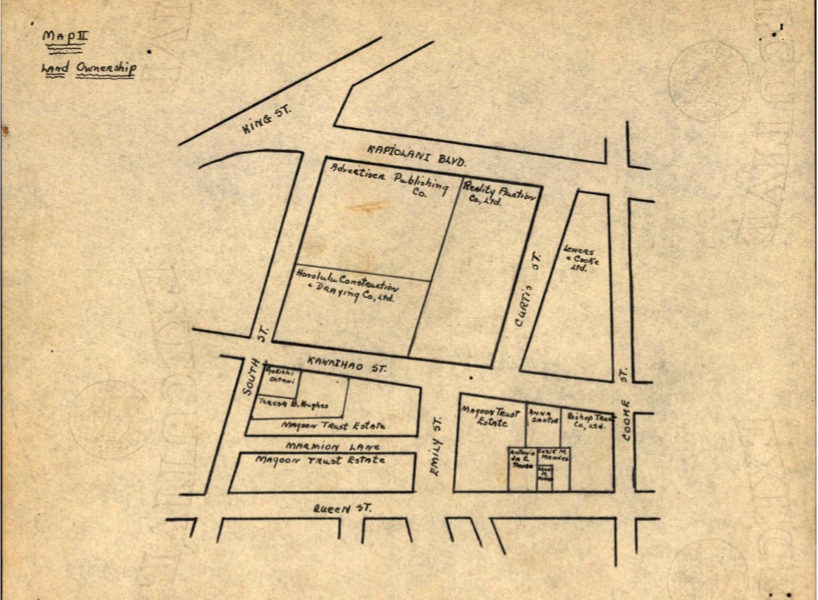

Map II provides the names of the property owners. Magoon Trust Estate owns most of the block bordered by South, Kawaiaha‘o, Emily (named after a Magoon daughter), and Queen streets with the block intersected by Marmion (the name of a Magoon son) Lane. The Magoon family owns part of the adjacent block as well.

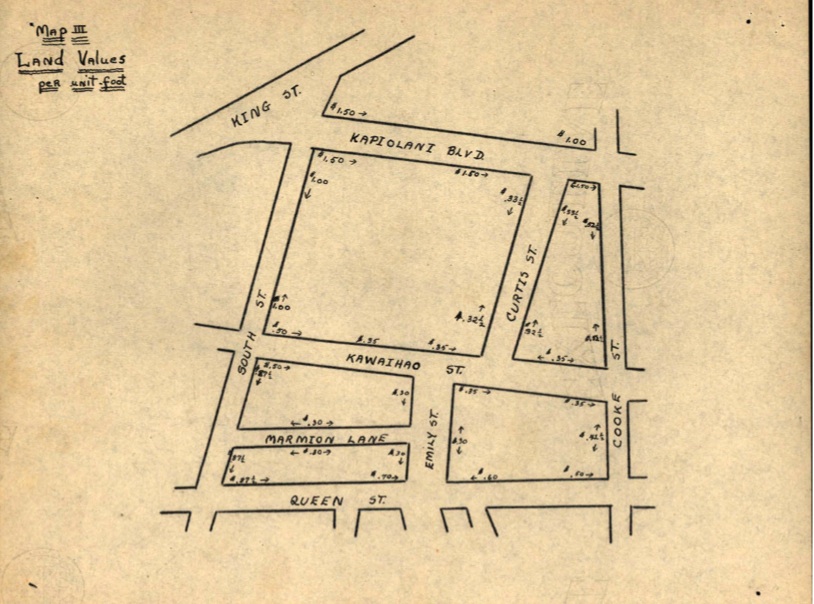

Map III lists the land values in the area. Mauka and makai on Kapi‘olani and Ewa on South Street between Kapi‘olani and Kawaiaha‘o have higher land values. The authors comment that “the city seems to be expanding toward Waikiki . . .” and predict that the land values along Kapi‘olani will continue to rise.

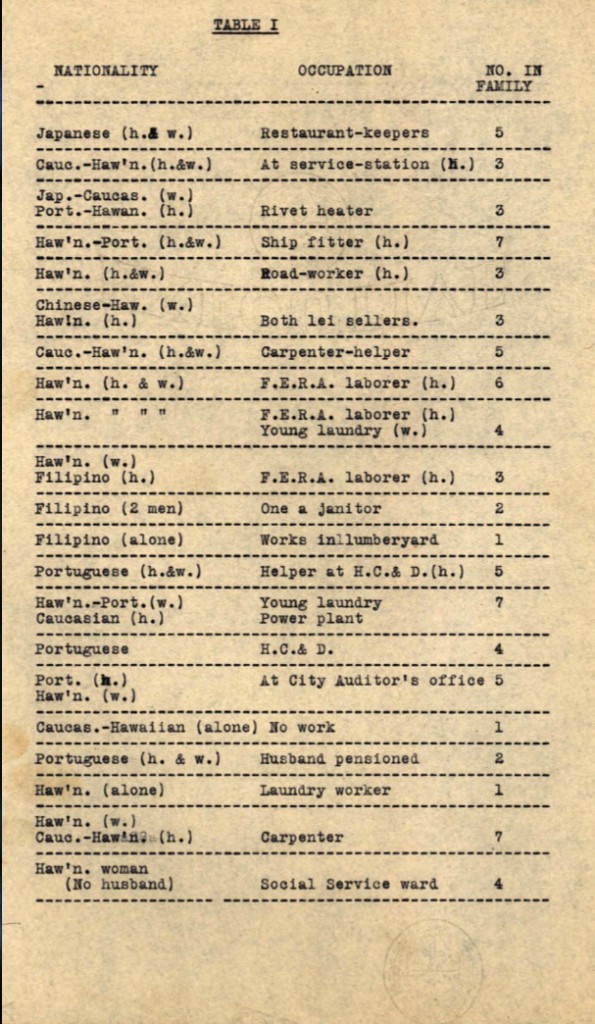

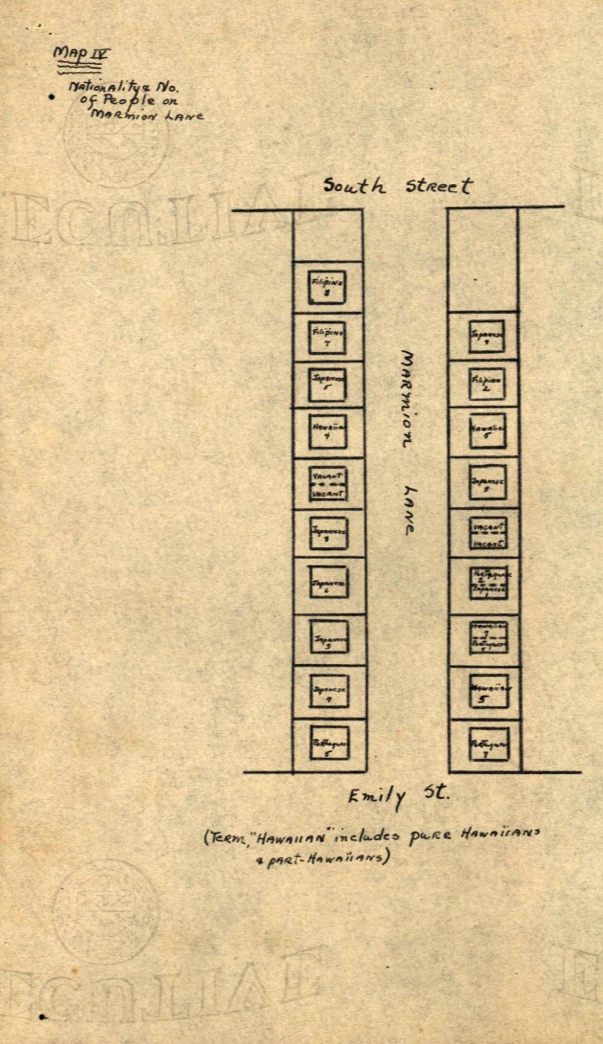

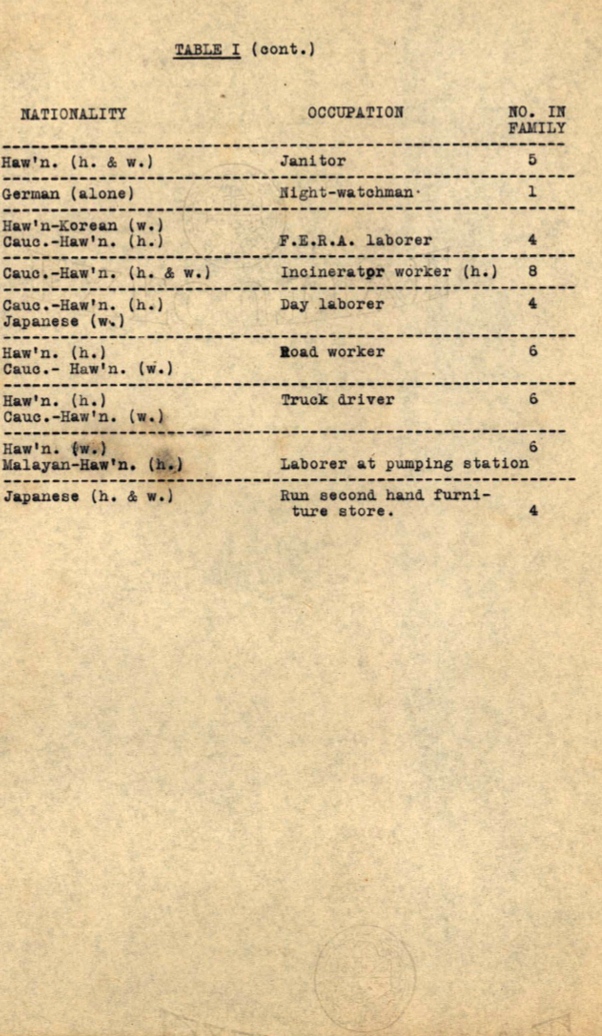

Maps I, II, and III, on onionskin paper, could have been traced from a Sanborn Fire Insurance Map to make rendering easier. Map IV (above) looks like an original drawing, showing the cottages on both sides of Marmion Lane, the nationalities and number of occupants in each cottage. Noted at the bottom is this explanation: the “Term ‘Hawaiian’ includes pure Hawaiians as well as part-Hawaiians.” Following this map is Table I that lists nationalities of the husbands’ and wives’ or single individuals in each living unit; the occupations of the individuals’ and of the husbands’ and wives’. In the paper, the writers state that wives with no listed occupations are housewives. In a few instances, the names of the companies or agencies for which the residents work are noted. The number of occupants in each cottage ranges from two to fourteen.

The information in Map IV does not tally with that in Table I. Map IV shows nineteen stand-alone dwellings. Four of these dwellings are duplexes, providing a total of twenty-three units. Four units are marked vacant; nineteen units are occupied. Table I includes information on thirty families, individuals, or groups with a total of 106 people living on the Lane. However, when the numbers for Table I are added the total is 125.

Marmion Lane has a mix of families – Japanese, Portuguese, Filipino, one “Caucasian,” one “German” but is predominantly Hawaiian. Of the thirty listings here, twenty-one households have Hawaiians. Aside from the Japanese “restaurant-keepers,” the couple that runs a second-hand furniture store, and the Portuguese man who works at the City Auditor’s office, most residents are laborers – working at a service station, in a lumber yard or at H.C.& D., at Young Laundry, at a power plant, at a pumping station, and at an incinerator. Residents work on roads and as carpenters, janitors, a night watchman, a day laborer, a truck driver. One married couple sells lei. One fellow doesn’t work, a widow is listed as a “Social Service ward,” one husband receives a pension, and three men are employed by the Federal Emergency Relief Agency (FERA), which had been created to provide new unskilled jobs in local and state governments. Although the paper is undated, the years for FERA, founded in 1933 and dissolved in 1935, provides a date range for this paper.

The Paper

The paper includes more information about Marmion Lane residents’ occupations than Table I. We learn that one resident works for W.A. Ramsay, an electrical and mechanical business. The older boy in a Japanese family is a bookkeeper at Nippu Jiji Publishing Co., elevating his family’s status:

On talking to the landlord’s agent it was learned that this family is a more prosperous one and does not mix with the other people in the area.

Japanese women operate two dressmaking shops on the Lane; some Japanese girls work as maids in Mānoa.

In addition to collecting data on the residents of Marmion Lane, the writers comment on housing conditions. Four of the cottages house two families, each with their own living room and bedroom with a shared bathroom, kitchen, and porch. “During the time the study of the area was made the land owners reconditioned some of these houses and built in private bathrooms and kitchens for each family. . ..” A Hawaiian woman said this about her remodeled cottage:

“’Gee, was swell now. We got place to take bath. Nobody can look. Before everyone come look. Lousy, you know.”

Single unit cottages have four rooms and a kitchen. Cottages are rented unfurnished with water included, and the monthly rents range from $11 for a double cottage to $18 to $22 for a single. The cottages are close together and as one resident with a sense of humor said, “’Good place for swim when we get heavy rain.’”

The writers entered cottages and saw a range of housekeeping, from neat-and-clean to neglected. An agent of the landlord told the writers that residents took better care of reconditioned homes.

The Magoon Tenement, on Queen between South and Emily streets, is a forty-year-old building with approximately 139 people. Its ground floor includes a restaurant, poi shop, two groceries, two barbershops, a shoe repair, a second-hand furniture store, and a drugstore plus two apartments occupied by Japanese. Thirty apartments on the second floor face mauka. The tenement’s sagging veranda offers a place to hang wash, cool off, and talk. The front rooms face South Street and serve several purposes: “bed-room and living room, kitchen, and bathroom.” More prosperous residents have adequate furniture, an electric refrigerator, radio, sometimes an electric mixer. The less prosperous have fewer items of furniture, a kerosene stove, and a wood ice box. The tenement apartments house anywhere from a single resident to eight people.

The paper provides details about the tenement dwellers’ occupations. The majority of the men are unskilled laborers working at Pearl Harbor or for the City & County, occupations that may have weathered the Depression better than others. Several women are lei sellers; others work at American Sanitary Laundry. One woman with three children receives assistance from the Social Service Bureau.

As mentioned previously, Marmion Lane was a mixture of local people with Hawaiians predominating. But one of the older residents told the writers that in years past most of the residents were Japanese. Eight Japanese families remain, the writers note (although not according to the tabulation in Table I), one having lived in the same cottage for thirty years. Many families are multi-generational.

The writers also observed the “habits of the people” in the area. They note that the Hawaiians and Portuguese are more “sociable” than others, but gossiping is kept to a minimum. Residents report gossipers to the landlord who then evicts these “troublemakers.” Disputes between families are rare, although the writers witnessed women having a heated argument about one woman’s chickens coming into another’s yard and eating the leaves off her plants.

The writers interviewed some residents and the landlord’s agent with the intent of learning about “length of residence, gossip, age of buildings, neighborliness, attitudes toward life, etc.” Although the writers were unable to find “any outstanding characters in the area,” they did learn about a Hawaiian woman who was known as the best-liked person on the Lane. She is so popular that families compete to rent the other portion of her duplex. Stereotypes invariably surface in RASRL papers, no matter how hard writers strive for an objective tone. These writers dutifully added that the Hawaiians are known for their “congeniality and affability.”

Except for the Portuguese who attend Catholic church regularly, most others in the neighborhood are not regular church attendees. Some of the Hawaiian children attend Aloha Sunday School and Christian Endeavor meetings. The children below school age play on the sidewalks, the streets, in yards, and in a “ditch” that runs through the area. Elementary-age children attend Pohukaina, the district school, and middle and high schoolers, Central Grammar and McKinley High School or Roosevelt High, an English Standard School. The writers said the source of residents’ amusement is sitting on their porches or attending the [Aloha] theater on Queen Street.

The writers conclude with this: “As a whole [the residents] seem very happy in spite of their poor living conditions and low standard of living.”

The Writers and Their University of Hawai‘i Context

According to UH’s yearbook, Ka Palapala, both M.N. and G.F. were members of sororities. The former belonged to Ka Pueo (1934–1936), a sorority for Haole, and the latter to Ke Anuenue (1935) for Hawaiians. In 1936, M.N. also served as Ka Pueo’s representative to the Associated Women Students (AWS). M.N. is not listed as a member of the 1936 graduating class nor does she appear in UH’s yearbooks for the next several years. She does show up as a student at the University of Oregon in 1937 (L. Davis, personal communication, 9/25/15). G.F., who is from Hilo, is listed in the 1935 graduating class with a major in General Science; she is one of twelve women out of sixty-three seniors in the College of Applied Science. Both writers had attended Honolulu’s Punahou School at the same time (Davis).

From its inception, UH allowed race-restricted sororities and fraternities. The Chinese Student Alliance, the first, was the only ethnically restricted student organization in 1920, the University’s first year of existence:

It is the aim of the Chinese Student’s Alliance to enlist every one of these students within its ranks. The Alliance aims to bring these students together that they may have that mutual understanding and cooperation for the great field of work awaiting them both here and in the Far East. … Right now the problem of Americanization seems paramount in Hawaii. The question is often asked: Can the Hawaiian-born Chinese or Japanese be Americanized? Can they become good citizens under the Stars and Stripes? There is no doubt that they can become good American citizens (Ka Palapala, pp. 48, 95).

At least in the early years, race or ethnic-exclusive sororities and fraternities were more a gathering together of minority students than an exclusion of others. The Chinese Student’s Alliance saw its goals as providing support for the few Chinese students on campus, creating an organization for members to develop leadership skills and to demonstrate their worthiness to be considered full-fledged Americans. Although unstated, it is likely that another goal was to recruit other Chinese students to UH.

By the 1930s when the writers were members, sororities, especially those exclusively for Haole, were decidedly more of a co-curricular social outlet for its members, while ethnic sororities and fraternities offered students a way to perpetuate and exhibit pride in their culture. By 1968, which was the last year Ka Palapala featured sororities and fraternities, many of the ethnic-exclusive organizations still existed on campus, but just as many other organizations made a point of describing their membership as “cosmopolitan” and open to anyone.

For women on campus, gender segregated organizations allowed them to observe and interact with women in important leadership positions on campus. G.F.’s affiliation with Ke Anuenue would have given her intimate contact with Dorothy Kahananui (featured elsewhere in this exhibit) who was the club’s adviser. M.N.’s membership in AWS not only put her in touch with her peers who were women leaders of campus organizations but also in close association with Dr. Leonora Bilger, adviser to AWS, chemistry professor, and UH’s Dean of Women. Bilger was the first and only one to hold this position at UH. In Notable Women of Hawaii, Madeleine J. Goodman provides a biographical sketch of Bilger:

It is in the position of dean of women that she is best remembered by the many alumnae who passed through her charges and came to think of her quite naturally and somewhat derisively as “Ma.” By all accounts, Bilger relished her position as moral guide, taking her responsibility of being in loco parentis quite seriously. Undoubtedly patterning her conduct on the Cambridge model, Bilger enforced curfew (10:30 p.m.), searched dorm rooms for contraband (mainly finding overdue library books), and on occasion delivered diatribes against the evils of interracial dating. She also gave advice and money from her own pocket to students whom she judged to be in need of the one or the other. President Crawford’s decision in 1937 to abolish her position and appoint a male director of personnel led to an unsuccessful protest to the Board of Regents by 350 undergraduate women (Madeline J. Goodman, Notable Women of Hawaii , Ed. Barbara Bennett Peterson, UH Press, 1984, p. 35).

Although UH had female students from the beginning, by the 1930s women were coming to the campus in what must have seemed like droves. In 1930, 31% of the senior class was female; by 1935, women constituted 48% of seniors. In the 1930-31 academic year, Teachers College became part of the University, likely the decisive factor in the increase of women on campus.

Social Historical Context

The writers conducted their study in the midst of the Depression, yet make no mention of it. RASRL writers rarely mention larger events examined in histories of the Territorial period for a number of reasons: perhaps these events weren’t relevant to the assignments or perhaps faculty asked them to focus on what they observed firsthand, what they intimately knew and not bother with the rest. What is interesting in M.N. and G.F.’s paper, however, is the relatively mild effect the Depression seems to have had on the residents in this part of Kaka‘ako. Only a few have jobs with FERA; one man has no work; and a widow with three children is receiving help from Social Services. All the rest are employed. They may have been working part-time or for reduced wages, as was the case for many during these hard times, but they were working.

Several of the residents were employed by the American Sanitary Laundry. This Magoon family business was located on nearby Queen Street. The Magoons have an interesting history. Chung Afong, who is often referred to as the Merchant Prince, arrived in Honolulu in 1849 and became, over the next several decades, “an eminent Chinese entrepreneur.” He served “as China’s first official representative to the Hawaiian Kingdom” (Robert Dye, “Merchant Prince: Chung Afong in Hawai’i, 1849-90,” p. 23). Afong’s marriage to part-Hawaiian Julia Fayerweather brought little money to the marriage, but “she did bring access to family land and strong ties to the reigning Kamehamehas and, of course, to Kalakaua” (Dye, p. 3). The couple’s eldest daughter Emmeline married attorney John Alfred Magoon. Not only did John found one of the first laundries in the Territory, but the Magoons also held significant shares in Consolidated Amusement Co. and of course owned land in the Kaka‘ako area.

In an oral history Genevieve Magoon, wife of Eaton and fourth son of John A., recounts her experiences when in 1936 she first began working for the family business due to Eaton’s illness.

I was soon charged with seeing that our rents were promptly paid. Take the land, Kakaako, for instance. We had many tenants there in “Magoon Block,” and the cottages. I didn’t even know where Kakaako was located. But I found someone to drive me there, and with a yardstick and a tape measure we made these little maps traced from the Sanborn Insurance Map (which gave buildings and street numbers). Then I found out who was staying where. This was also true in the tenant area, often referred to as “Magoon Block.”

In those days we had collectors in charge of collections for various areas where the company owned property. Well, we had a collector in Kakaako who was a favorite. And so I called him in and said, “I’m trying to find out (I had a map, something like this) who stays where. And I went down there and talked to some of the people, and they said they had two names. What does this mean?”

The nice old man broke down and started to cry. I said, “Why do you feel so bad about it?”

He said, “Mrs. Magoon, all my life I been cheating J. Alfred Magoon . . . and now his office. And I can’t stand it any more. I got to tell you.”

So he cried, and I cried. We both cried.

I learned he had a separate account book of his own, (where he charged each of say, a 100 Kakaako tenants under their fictitious names, a dollar or so more a month than monthly rents shown on our books under their correct names, pocketing the difference each month, over many years. He was so old and so broken that he was given a chance to return to his homeland (Gael Gouveia, “Oral History Interview with Mrs. Genevieve Eaton Magoon,” Magoon Estate Ltd., Office Honolulu 10/4/77, pp. 761-2).

Perhaps the “landlord’s agent” the writers interviewed was the man who had been cheating the Magoons for years.