The Paper: “My Neighborhood and Its Relationships with Institutions in the Surrounding Area,” mid- to late 1930s

The Writer: B.C.

Location in RASRL: Lind Box 9 Student Papers/Maps (4), #10

The Writer

The 1939 issue of Ka Palapala lists the author as a member of Teachers College Club; the YWCA; the Episcopal Club; and Hui Iiwi, a woman’s glee club advised by Dorothy Kahananui. B.C. was a member of the 1939 graduating class with a major in Secondary Education. When she wrote this paper, she was teaching Sunday school at St. Peter’s Episcopal Church on Emma, now known as Queen Emma, Street.

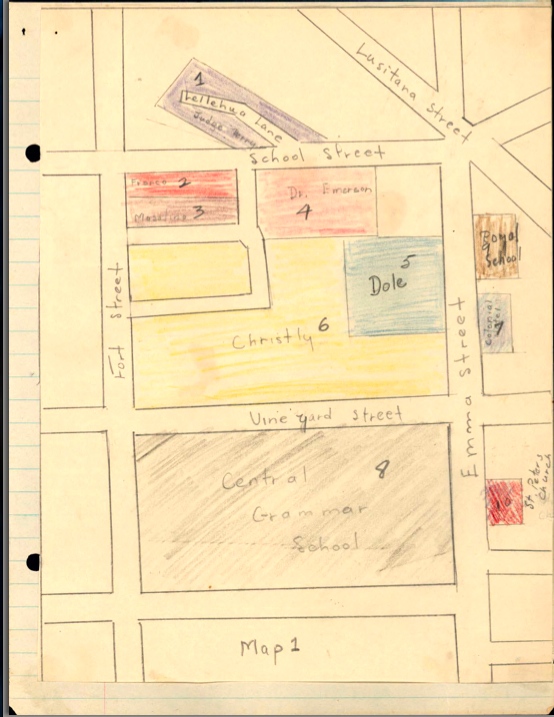

The Maps

For her neighborhood report, B.C. drew two 8-1/2 by 11 inch maps. Map 1, in color, indicates previous owners of tracts in the area: Judge Antonio Perry; (likely Joseph A.) Franco; Masalino; Dr. [Nathaniel B.] Emerson; the Dole family; and Christly. Next to Royal School is the Colonial Hotel, which was owned by J.A. Campbell. B.C. didn’t note the years that the tracts were sold to make way for “middle class” housing, but a current real estate advertisement for Leilehua Lane features a dwelling built in 1924, about the time her family would have purchased a home in the area.

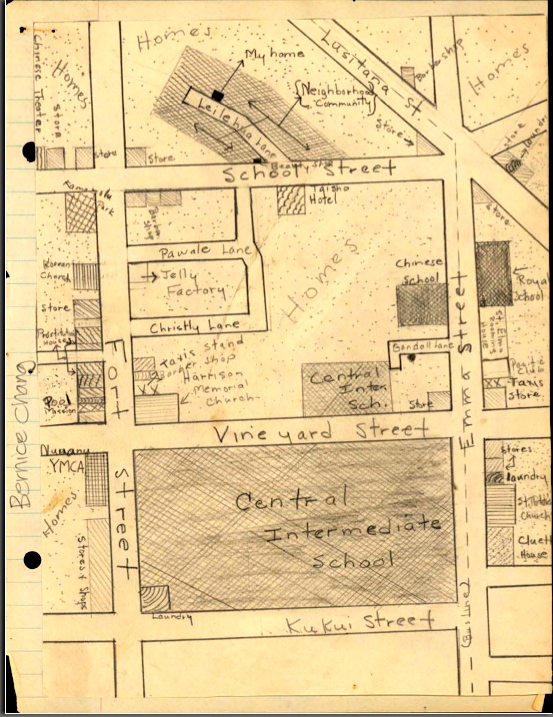

The second map, in black and white, illustrates B.C.’s neighborhood as she knew it. What were once large tracts of kama‘āina landed estates in Map 1 became a neighborhood of homes predominantly owned by Chinese. Within easy walking distance of downtown Honolulu, B.C.’s neighborhood offered a range of shops, businesses, and schools. The area had three churches to serve the Chinese, Japanese, and Korean communities. This predominantly Chinese neighborhood had a Chinese language school, located across from Royal School. B.C.’s map shows the Nu‘uanu YMCA, on the corner of Fort and Vineyard streets, and the Pacific Club, wedged between a taxi stand and St. Elmo’s Rooming House.

RASRL neighborhood maps, hand-drawn by the writers, are personal and therefore unofficial. B. C.’s map, like others in this exhibit, has errors: Harrison Memorial should be Harris Memorial, and Christly likely should be [Judge Albert] Cristy. Some names of stores and shops are omitted when presumably she could have easily included them. But this is not to suggest that these maps are of little use. Personal mappings of neighborhoods provide insider knowledge of places that official maps don’t or can’t. For example, the lanes of Gandall, Pawale, and Christly no longer exist and even Pukui et al.’s Place Names of Hawaii (1974) doesn’t mention them. B.C.’s maps provide evidence of places that were subsequently razed for development.

The Paper

Handwritten in pale blue ink on lined ecru-colored paper, this paper focuses on Leilehua Lane, located in lower Punchbowl and, as the writer points out, is also known as the ‘Auwaiolimu area or ahupua‘a. B.C.’s interest is in showing the changes the neighborhood has undergone during her more than thirteen years there. RASRL’s neighborhood papers often present shallow histories, ones that don’t extend much further back than the arrival of the writers’ families. B.C.’s paper is different in this respect: she offers little about her family and instead takes a comparative look at her neighborhood. Before Leilehua Lane and its surrounding neighborhood existed, the likes of Dole, Emerson, and the family of Princess Kawānanakoa lived in an area that in B.C.’s time were single family homes mostly Chinese-owned. She also briefly traces the histories of Royal School and the Normal School, institutions that would interest a future teacher.

B. C. says in the past thirteen years the area had experienced rapid growth with the arrival of major institutions – three churches; two public schools; a language school; and the Nu‘uanu YMCA. There is a jelly factory; four laundries; a playground; a clubhouse; hotels and boarding houses; a Chinese theater; and a prostitute’s house. Housewives do not need to leave the neighborhood to purchase groceries, she says, although a bus line does run on Emma Street. Neighborhood grocers make home deliveries and the vegetable seller visits daily, calling out “Mi choy (selling vegetables)” as he pushes his cart down the lane.

B.C. says that twenty-one families, mostly Chinese, own homes on Leilehua Lane, although there are a handful of renters. Because these families all have some kind of relationship that predate their becoming neighbors, the neighborhood is quite stable. She enumerates sociological characteristics of the Lane: the Japanese group is isolated, although not unfriendly or shunned. The “we” group are Chinese, some of whom are blood relatives. There are two Portuguese families, and a woman of one of these households has this to say about the neighborhood:

I like this place because the neighbors don’t bother me. I live here at the end of the lane carrying on my own doings and bother no one else. I bought this home when I came from Oakland, and I aim to stay here as long as I can.

The other Portuguese family is snubbed because of the “carrying-on . . .. She always has male company in her home and practically ‘raise the roof.’”

B.C. likes a particular Japanese family since “they do not bother you at all and are nice neighbors.” She adds that gossip is an outstanding feature of some Chinese families:

The social inter-relationship is on such intimate terms that if you whispered some spicy gossip to any one of the members of this group it spreads faster than “bush fire.” They have a favorite rendezvous for the purpose of exchanging gossip. . . Every evening after supper these old Chinese immigrant women or even their daughters gather [under a tree] and talk.

She takes particular notice of the youth in the neighborhood. A family of four boys and one girl whose mother recently died has fallen apart: the girl ran away and married leaving

the boys to manage the house. The boys tried to hang on but could not do it. They could not cook or anything so the family broke up. One of the boys had a whim of always getting into trouble and landed in jail. He has served two short sentences and is still serving his third.

Although the YMCA was nearby and Boy Scout troops were active in the area, there was a gang of boys who hung out all day near Central Intermediate near Vineyard, a group with whom she seems to have an easy relationship. B.C. said sometimes they are singing, other times playing cards, but often they sit “there all day long, practically doing nothing.” These same boys gamble at the home of one of their “gang” members or frequent the pool hall. Even the mission that is two doors away from the pool hall, she says, has no beneficial effect on the boys.

This neighborhood continues to be in transition:

There were two prostitution houses in Fort Street about two months ago. Now there is only one left. . . . They are gradually being pushed out of this area or rather have moved to [an] area better fitted for them.

She describes several rooming houses in the area, from the bungalows of St. Elmo’s to the Cluett House, which is managed by the Episcopal Church and rents to working women. Taxi dancers rent rooms at Taisho Hotel. Another rooming house on the Central Intermediate block rents to stevedores, “pick and shovel laborers,” and taxi dancers but is being “taken away from the owners and is now being used by the school as a classroom. This will change the appearance of that area considerably.”

B.C. is describing a neighborhood that is not entirely urban, not quite suburban. She mentions that the park (Kamāmalu), at the busy corner of Fort and Vineyard, is a place where she wasn’t allowed to play as a child. Now that the park has been enclosed by a wall, it is safe for children to use. But progress also has had its costs. Her church, St. Peter’s, has experienced a decline:

I remember those days when the Sunday school was quite a large one. The membership was about two hundred but now there are no more than sixty boys and girls combined. The church congregation is even worse. . . . Rev. [Yim Sang] Mark told me once that he used to baptize almost four to five new members every three months but now that same number may take more than eight months, sometimes even a year. This church has hardly no influence on the neighborhood community.

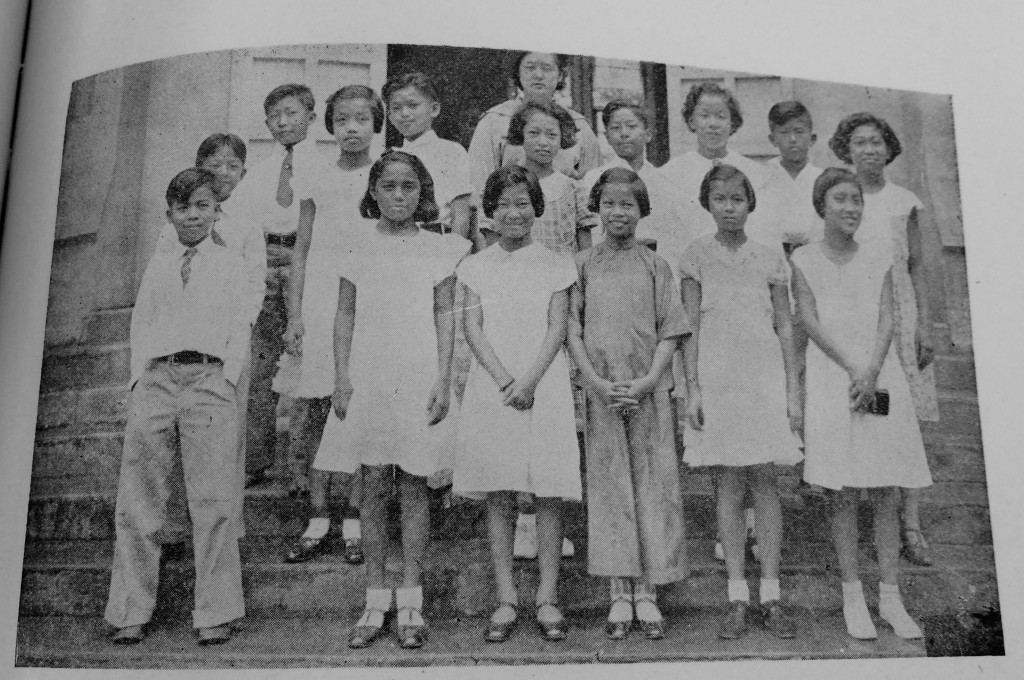

In Rev. Mark’s St. Peter’s Church: An Historical Account of the First Chinese Episcopal Church in Hawaii: Fifty Years of Fruitful Service and Progress 1886 – 1936 (1936), B.C. is listed as a member of Sun Te Hui, presumably a church youth group, and as mentioned previously, taught Sunday school class.

Sunday School class, Rev. Mark’s St. Peter’s Church: An Historical Account of the First Chinese Episcopal Church in Hawaii

RASRL Context

Even though B.C. was involved in campus organizations, she was a commuter student living at home and an observant resident of Leilehua Lane and environs. She actively worked with youth and was sincerely interested in their welfare, the mark of someone who would make a dedicated teacher.

As part of community studies, students were asked to notice and explain social control or gossip. As someone who valued “not being bothered,” the neighborhood gossips irritated her. As often reported by RASRL writers, young people were particularly vexed by spying neighbors who seemed to delight in letting parents know when their children misbehave.

Social Historical Context

Although B.C. only briefly mentioned the YMCA, she probably was aware of its importance to her neighborhood. In The Y.M.C.A. in Hawaii 1869-1969 (1969), Gwenfread Allen says: “It is hard to overemphasize the role which the Nuuanu Y.M.C.A. played in the lives of many boys from humble homes with immigrant parents.” Allen includes comments from US senator Hiram Fong who said the Nu‘uanu Y was “his second home” (p. 67). Senator Daniel Inouye says his connection to the Y was from birth.

. . . I was born on Emma Street, just a few steps away from the corner of Vineyard and Fort . . . Were it not for the “Y,” I might, like some of our less fortunate in Hawaii, be carrying a prison number after my name instead of the title, “United States Senator” (pp. 67-8).

The YMCA describes the Nu‘uanu branch as the “world’s most notable achievement in racial integration.”

The Y’s variety of educational and recreational programs alone were a strong attraction to young men. But the Y also drew members from Hawaiian, Chinese, and Japanese students who attended the Honolulu Bible Training School as well as from other Asian organizations. Allen says that these boys didn’t have a place in English-speaking churches, dominated by Haole, or foreign-speaking “racial” churches. “They accept the YMCA as a substitute for church” (pp. 104-05). What B.C. might not have realized was how the Y was drawing young people away from St. Peter’s.

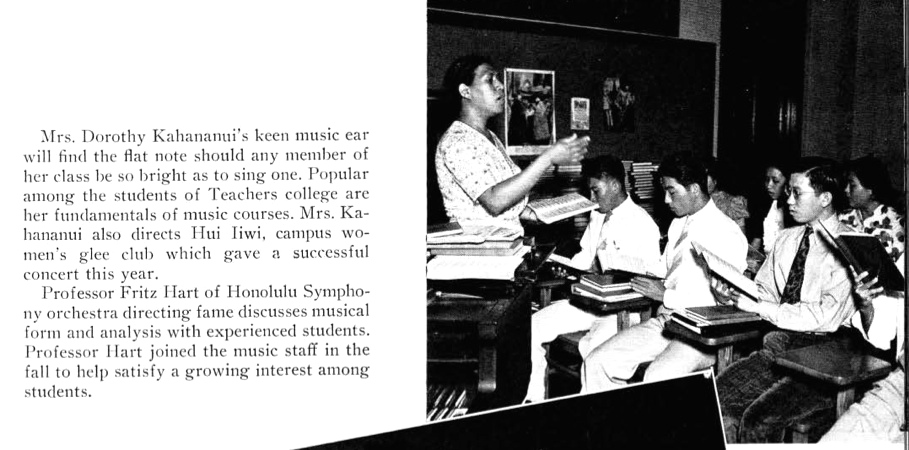

What makes some writers more sensitive, more aware of the deeper past? B. C. made no mention of Hawaiian neighbors who might have shared what they knew about the area’s past; she claimed no Hawaiian ancestry. Yet she acknowledges her neighborhood as situated in ‘Auwaiolimu ahupua‘a. Maybe the organizations to which she belonged made the difference. As a secondary education major she may have studied Hawaiian history or made friends with Hawaiian students enrolled in Teachers College. Perhaps it was her membership in the YWCA, an organization that, like the YMCA, prided itself on being open to all regardless of race. But her awareness of and interest in the Hawaiian past may have been due to Dorothy Kahananui. B.C may have taken music courses from Kahananui who taught all ten music courses offered in UH’s Teachers College. She certainly would have had regular and intimate contact with Kahananui who served as advisor to the glee club of which B.C. was a member.