The Paper: “Sociological Study of Kahului Maui,” mid- to late 1930s

The Writer: H.M.I

Location in RASRL: Lind Student Papers, Box 1, Folder 2

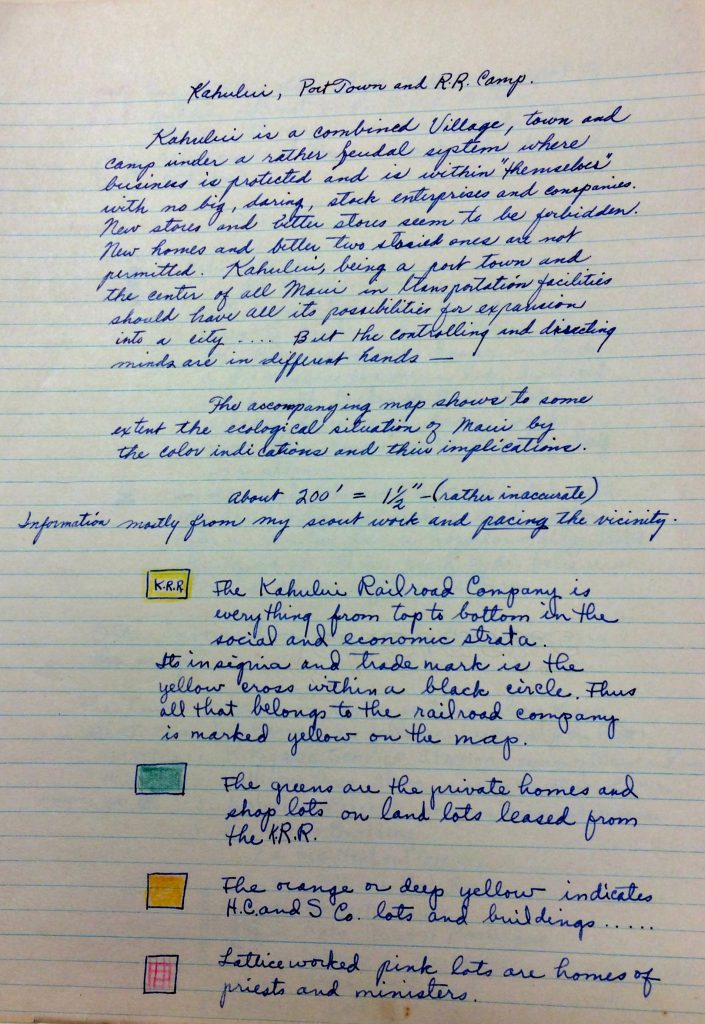

This map of Kahului – roughly 2½ feet by 3¼ feet with a scale of about ½ inch for 200 feet – was drawn on brown wrapping paper. The writer says she obtained information mostly from “scout work” and by “pacing the vicinity.”

In the opening section of her paper, H.M.I. explains the map’s codes and lists the names of residents and merchants and where they resided. Even a quick glance at the map reveals the main reason for Kahului’s existence:

The Kahului Railroad [K.R.R.] Company is everything from top to bottom in the social and economic strata. Its insignia and trademark [on the map] is the yellow cross within a black circle. Thus all that belongs to the railroad company is marked yellow on the map.

She explains the other colors:

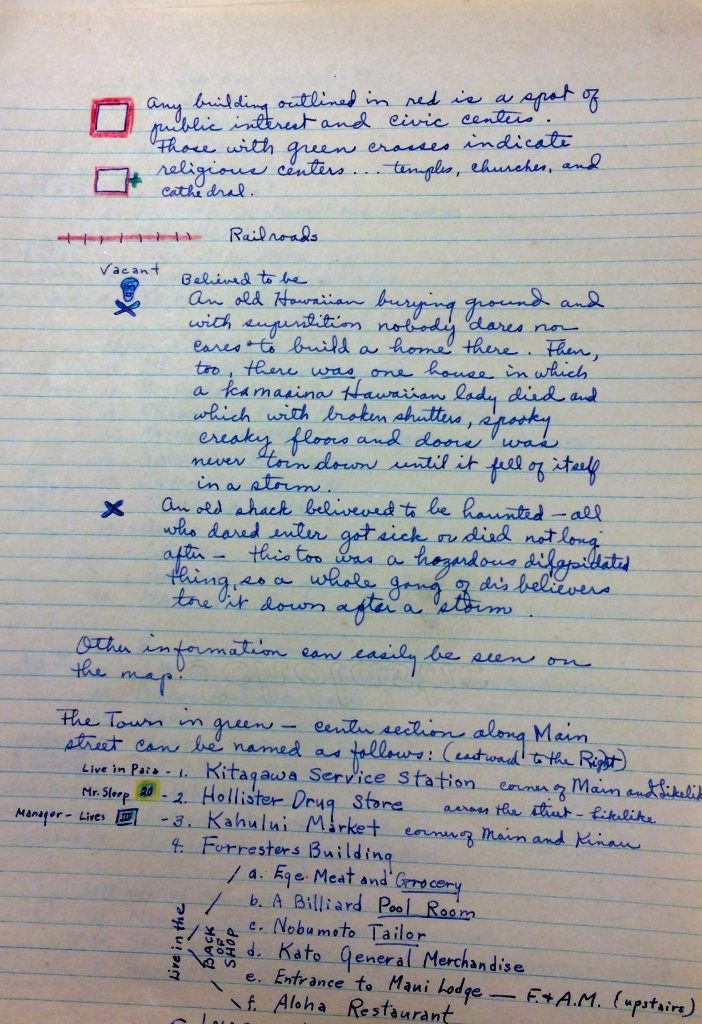

Red lines with black hatches indicate railroad tracks. On the map’s left, the tracks come from the direction of Wailuku, run parallel to Main Street toward Pā‘ia, and then fan out and multiply to serve the two piers on Kahului Bay (map’s top right). Another set of tracks at the bottom right serves neighboring Pu‘unēnē and its Mill.

She also includes items of local lore that only a long-time resident would be privy to. The skull and crossbones marks a vacant lot “believed to be an old Hawaiian burying ground. … there was one house in which a kamaaina Hawaiian lady died and which with broke [sic] shutters, spooky creaky floors and doors was never torn down until it fell of itself in a storm.” The “X” is “an old shack believed to be haunted – all who dared enter got sick or died not long after. …” Because it was “a hazardous dilapidated thing … a whole gang of disbelievers tore it down after a storm.”

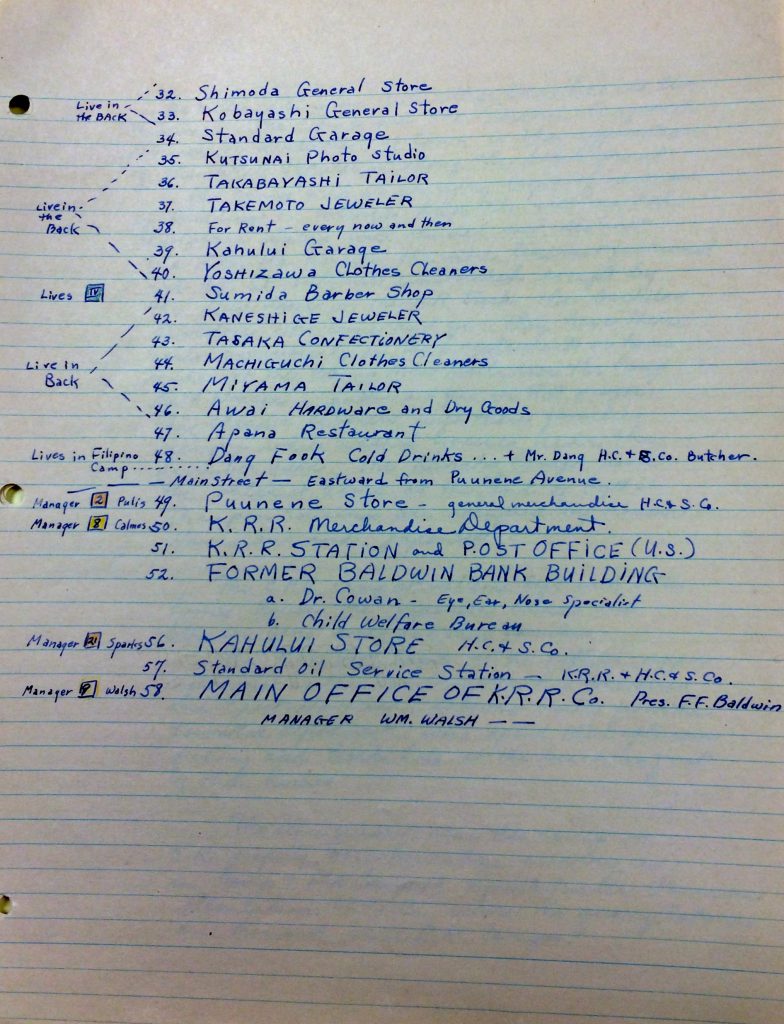

The writer likely relied as much on Kahului’s city directory as her insider knowledge. (She was a daughter of one of Kahului’s shop owners.) She provides not only the types of establishments and the names of merchants but also whether they live in the “back of shops”; in Kahului, Pā‘ia, or Wailuku; or like the butcher for H.C.& S. Co. in “Filipino Camp” (item 48, left side of Pu‘unēnē Avenue). She adds additional details: Okada Fish Market (14, upper Main Street) rents rooms to “bachelors” and Shimoda Dressmaker (30, left side of Pu’unēnē) lets apartments to Maui Pine workers.

Kahului offers a full range of concerns, some of which enjoy a fair amount of competition: ten general merchandise and hardware stores and one drug store; seven restaurants, one coffee shop, and one confectionary; five markets (meat, grocery, fish); four tailors and one dressmaker; three barbers; two jewelers; two clothes cleaners; two service stations and two garages; two hotels and two poolrooms. Kahului, like any town worth its salt, has its own photography studio.

First Street runs along the Bay’s beachfront with its “Haole Beach” and the “public” beach to the right of it. Number 9 is the home of William Walsh whose residence the writer has emphatically labeled “BOSS.”

Then in the back of this all along the Second St. are the better homes of the Haole population – beach bungalows and palaces occupying the block – the front yards facing First [S]treet (a path along the beach line) and spacious backyards… .

H.M.I. says Kahului, “a R.R. village,” is divided into “the Camp and the Town. … The camp with its varying degrees of newness of buildings or cottages keep the well-marked economic status well divided and distinct.” She describes older houses as tenement-like and inhabited by field hands and “bachelor stevedores.”

[The stevedores] have their meals luxuriously in town restaurants or homemade at the camp mess hall near the camp bath house [on Third Street], public and free for R.R. people.

Other laborers and their families live in whitewashed houses near the lumberyard, the Kanahā Camp, and the camp at the left end of Fifth Street. “These poor housings [sic] are occupied by Koreans, Hawaiians and Japanese.”

At the C.P.C. (California Packing Corp.) Camp, the extreme left (near Kahului School), are the better homes of Japanese luna and stevedore “gang heads” and their families.

The Raw Fish Camp, at the extreme upper [left] just as the name implies, has Hawaiian and part-Hawaiian laborers mostly from the locomotive department, who spend their afternoons fishing and huki kolo [*] at the beach in front of their homes.

*The writer has penciled in “Hukikolo Beach” on the left side of the Bay, a location that doesn’t appear in Mary Kawena Pukui’s Place Names of Hawaii. Next to this, H.M.I. has written “hukilau.” Huki kolo Beach may have been the name for the site where hukilau nets were stored.

The K.R.R. Camp is located near the quarry (which may be the “stone crusher” at the top left on the map) and the residents include quarry workers, railroad watchmen and flagmen, as well as “youthful strong stevedores and their families [and] the higher white collared second generation clerks (living near the public school in the new larger houses) and bookkeepers and first generation lunas.”

Mostly middle class Japanese laborers – truck drivers, some stevedores, clerks, bus drivers – live at a camp above Third and across Likelike streets. She says it is the camp’s gossip center:

News flies faster than fire here and spreads bigger and bigger and wider and when it reaches the extremities of town no head nor tail can be made of that tale.

She explains that Japanese employees and laborers comprise 40 percent of Kahului’s population, and in 1935 numbered, along with “town Japanese,” 1,451. A few Haole managers, Chinese, who are mostly clerks, and some Filipinos, Portuguese, and “mixed people” make up the rest of the population, for which the writer offers no figures.

Facing Main Street is what she calls “Porrikee Camp.” These Portuguese, Spanish, Hawaiian-Caucasians residents, she says, work for the train and truck department and have large families.

No doubt because the amount of detail is nearly overwhelming, the writer does not explain all items shown on the map. For example, we are intrigued by but left to wonder just what was the purpose of “Joy Zone,” located at the bottom center of the map.

This poem-like note acts as a preface to H.M.I.’s paper. Whether feudalism is the most apt term to describe Kahului’s social and economic structure or not, it is one that best expresses this writer’s sense of unfairness and her indignation:

This poem-like note acts as a preface to H.M.I.’s paper. Whether feudalism is the most apt term to describe Kahului’s social and economic structure or not, it is one that best expresses this writer’s sense of unfairness and her indignation:

Kahului is a combined village, town and camp under a rather feudal system where business is protected and is within “themselves” with no big, daring stock enterprises and companies. New stores and better two storied ones are not permitted. Kahului, being a port town and the center of all Maui in transportation facilities should have all its possibilities for expansion into a city. But the controlling and directing minds are in different hands. … K.R.R. is alert and always jealous of strong competition so they never allow any parallel or similar businesses to come into Kahului nor let people who work for those companies other than the R.R. and its affiliation have any say in living on R.R. land lease.

When the writer turns her attention beyond industry to the lives of the community, she writes enthusiastically and with pride.

An interesting organization of Young Men called the Kahului Japanese Young Men’s Association has its club house … on Fourth St. It was organized about 10 years ago. It has a wide appeal for boys 15 to 35 years with the purposes of civic interests. … Some of its unique and interesting activities are as follows: 1. managing and financing funerals of old bachelors with no family connections 2. acting as police guards and night watchmen during a frenzy over a “ball of fire” and when there was a phobia of a loose convict from the Wailuku County Prison 3. amateur players and theatre guild – free and benefit movie entertainments [sic].

… on the corner of Main and Kinau is the largest market [Kahului Market] in Kahului, maybe of the whole island, too. Managed by Mr. Ooka, a former employee of the H.C. & S. Co. at Kahului Store. He learned his business and started this Fish Market, Meat Market, Vegetables Stands, Fruit Stalls and grocery market all under one “big top” with his own “cash and carry” department predominant. “It is a housewife’s shopping paradise!”

Social Historical Context

For the writer Kahului was first and foremost, for better and worse a railroad town. With the Reciprocity Treaty of 1875, Hawai‘i was able to export raw sugar to the US duty free. As Hawaii’s sugar industry expanded so did the building of railroads.

The first train ran on July 17, 1879, and scheduled service began in another three days. The venture went under the name of the Kahului & Wailuku Railroad and headquarters were in [Thomas H.] Hobron’s general store in Kahului. A year after the first three miles were finished it was decided to build eastward with Sprecklesville, Paia and Hamakuapoko in the new plantations as objectives (John B. Hungerford, Hawaiian Railroads: A Memoir of the Common Carriers of the Fiftieth State, p. 71).

Of course, I am proud of my home town and we all are for its decency, cleanliness, and well managed orderliness both economically and socially. But the whole machinery is on a plantation scheme and ruled with a rather autocratic iron hand. … Kahului, the Railroad Company’s Camp and Village under the management of Mr. William Walsh who is controlled by the H.C. & S. Co., Puunene manager F.F. Baldwin who more or less belongs with the Castles and Cookes and Damons and Athertons to the controlling mechanism of the Hawaiian Islands.

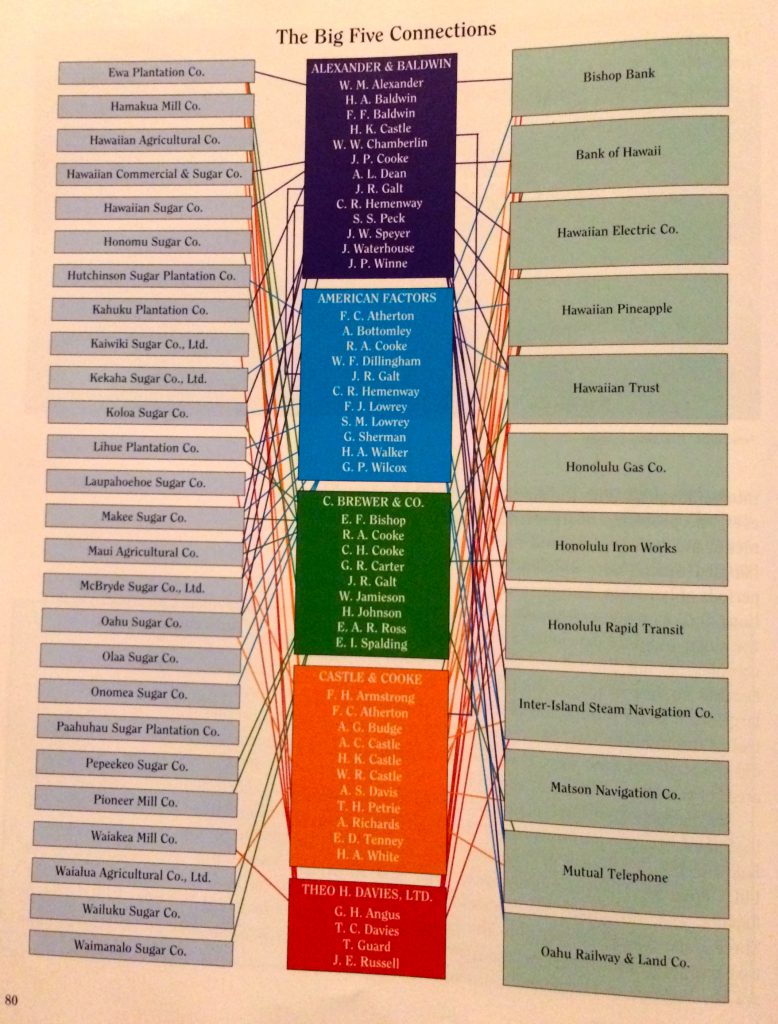

The writer is referring to Hawaii’s Big Five – C. Brewer & Co., Theo H. Davis & Co., Amfac, Castle & Cooke, and Alexander & Baldwin – and their “controlling mechanism of the Hawaiian islands.”

During the 1930s the so-called Big Five companies controlled thirty-six of the territory’s thirty-eight sugar plantations as well as banking, insurance, transportation, utilities, and wholesale and retail merchandising. Interlocking directorates, intermarriages, and social associations bound this financial oligarchy closely together. By 1940 a dozen or so men managed the economy. During the territory period, almost half the land was owned by fewer than eighty individuals, and the government owned most of the rest, producing a concentration of wealth and power more extreme than elsewhere in the United States (Gary Okihiro, Cane Fires, pp. 14-15).

Board membership allowed sugar leaders to influence a wide range of businesses, from large retail stores to newspaper agencies to hotels. This same group of men served on the boards of various community organizations, contributed to Protestant churches, belonged to the same clubs, socialized at the same parties, and sent their children to the same schools. Like the business associations, fellowship with the “proper” persons and affiliations with the “proper” organizations became important indicators of one’s status and power in Hawaii’s society (Rayson, pp. 84-85). These men not only strictly voted the Republican ticket but were the Republican party that controlled the Territory.

In his oral history, Katsugo Miho, a resident of Kahului and contemporary of H.M.I, presents a vivid example of Kahului Railroad manager William Walsh’s power and authority and Kahului’s social hierarchy:

I remember that I had to deliver — those days, basically it was, a gallon of sake is what was being delivered to Mr. William Walsh’s home, prior to every new year. Japanese style, your big boss or whatever, you have to bring gifts and annual end-of-the-year gifts to beginning-of-the year gifts. Everybody had to listen to whatever orders that came down from the manager of the railroad company and the stevedoring company, which was Mr. Walsh.

To give you an example, when I was working as a movie usher, our manager, Mr. [Felix] of the theater, would get completely excited when he was told that Mr. and Mrs. Walsh would come in and take in a movie on a Saturday night. And he would be so uppity and he would get after us ushers and, “Now, one of you get out on the road and look down,” because you could see [down] the road where the Walshes lived. “See if they’re coming out.” Then, by the time that they [arrived] — completely nervous.

And yet, the theater wasn’t owned by Kahului Railroad [Company]. It was owned by [Maui Amusement Company]. But the manager was completely out of his mind when the Walshes would come in to attend a movie. That’s the kind of life it was, probably like, comparable to the old plantation life in the South where the boss, the landlord, was the absolute boss. Well, Mr. Walsh was the absolute boss of Kahului.

RASRL Context and the Writer

Occasionally RASRL writers will comment on the challenges they faced in completing their community study assignments. If the community were on a neighbor island or even was a rural community on O‘ahu, the writer would need to visit the community to take notes, interview residents, walk the place, and they would need to rely on family, friends, and other members of the community to provide information for their report. As college students, they were by necessity living in Honolulu, usually holding down a job and carrying a full credit load.

H.M.I. prefaced her study with an extended apologia for what she likely considered work that may not have been up to her and the faculty’s standards:

First, the minister’s family with whom I am living, working for board and room, is a close friend of ours, Mr. Kingdon having been my pastor for seven years in Kahului.” Although the Kingdon family “is an irresistible and interesting study – both sociologically and psychologically. … Yet when it came to ‘ILLNESS’ it was another thing.

She enumerates the problems she faced: there was the measles epidemic in 1936 during Christmas, then Bobby Mac got bronchitis and Baby Henry had his “asthmatic croup attacks.” H.M.I. caught the flu then Mrs. Kingdon came down with it, as well as pneumonitis and pneumonia, eventually landing in Queen’s Hospital for six weeks. Then Mr. Kingdon had a heart attack. Since the writer relied on the Kingdons for information on the Haole population of Kahului, she admitted that she couldn’t very well quit her job with them “in the midst of this mire of hard knocks.”

But for H.M.I., far worse was the conduct of some of her classmates.

There have been several people “showing off” grand maps and projects of their “local home” on other islands and revealing that they did not have to do any hard work for [their] Sociology term paper, because their “boy friends” back home did all for them. “Handy cheating” I call that.

But H.M.I., in spite of the hardships, did complete the written assignment and produced a marvelously detailed map of her community. In 1939, she graduated with a bachelor’s degree in secondary education and went on to teach at Lāna‘i High School, which had only recently opened in 1938.