The Paper: “My Neighborhood” – ‘A‘ala, 1955

The Writer: #2095

Location in RASRL: Student Papers (Unprocessed) Soc 151 Student Journals 1955 Box d

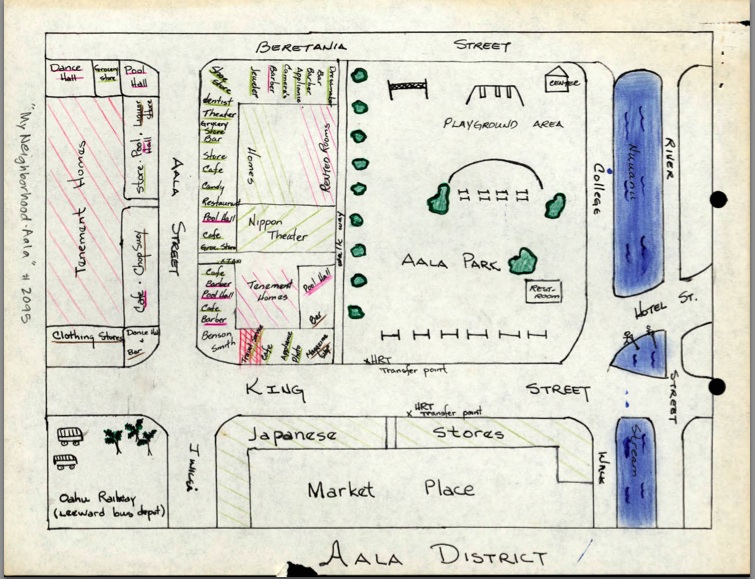

The Map and the Paper

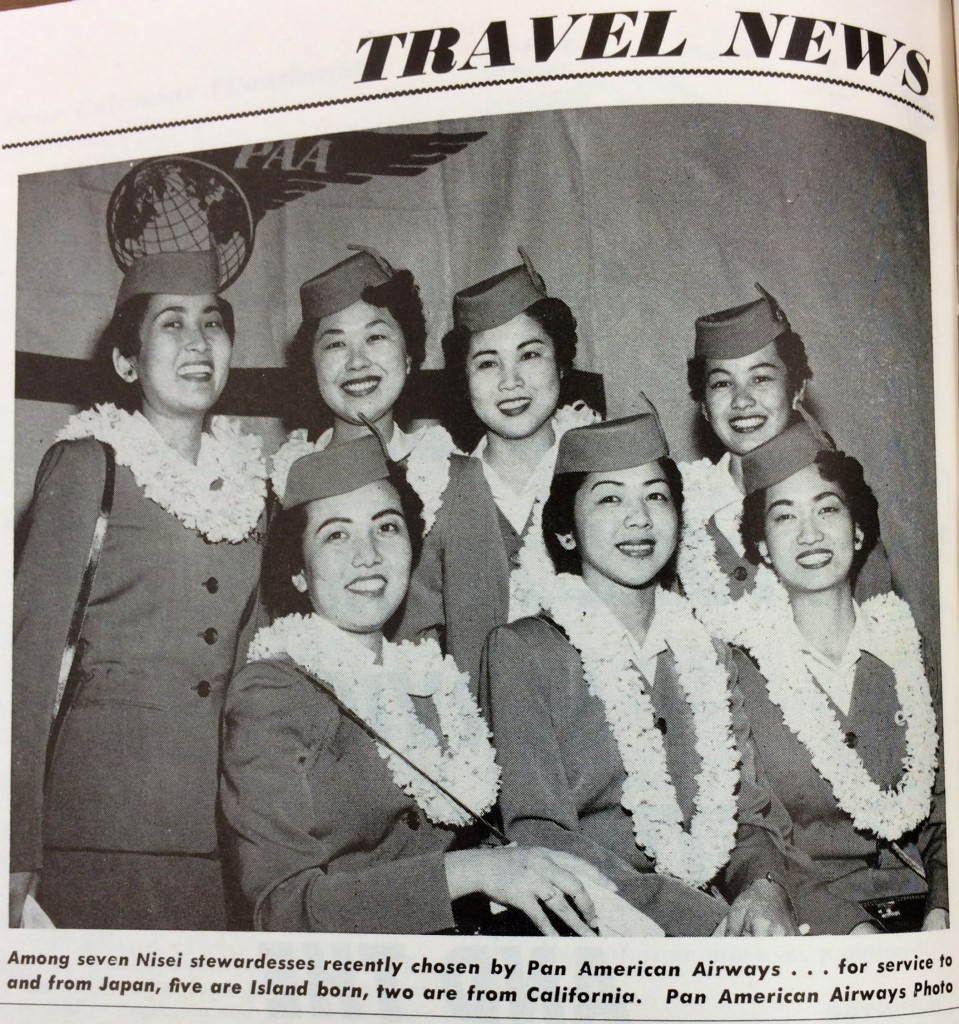

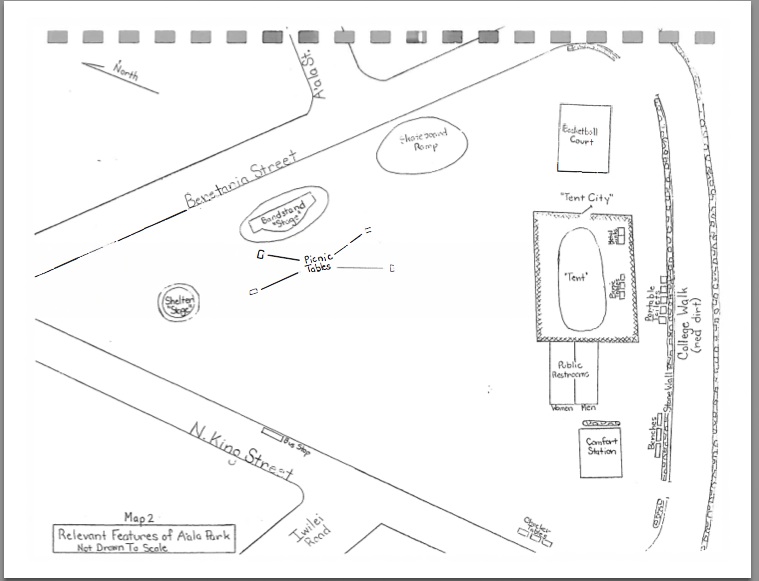

This carefully drawn map of ‘A‘ala Park seems inviting, almost bucolic with its playground equipment, volleyball net, recreation center, and bathrooms and scattering of trees. However, it’s a place Writer #2095 avoids because, as a young woman, the men who loiter there are “socially and economically low” and leer at her. As with most of RASRL maps, residents’ “races” are indicated by specific colors.

The writer considers ‘A‘ala Park, the district where she lives, as a “famous, but unfavorable landmark” in Honolulu and describes what she can see from her family’s rented second floor apartment above her father’s travel service, the red cross-hatched area on King Street near ‘A‘ala Street. At the bottom left on the map on King Street is the Oahu Railway Company building, which was a train depot until 1947 and by 1955 the Leeward Bus Terminal. The main transportation line through Honolulu with various transfer points is located in this area.

The ‘A‘ala history she offers is based on what she recalls from her childhood and perhaps what she has learned from her parents. She mentions the businesses that catered to servicemen and notes that a curio shop on the ‘Ewa side of River Street relocated to Hotel Street to capture the military trade. She wonders why servicemen didn’t cross River Street. “Hotel Street, the Service Man’s Domain” was the headline in the October 1943 Paradise of the Pacific. Its demarcations were River and Richards streets.

As a child, the writer would play in the grassy area under the coconut trees fronting the Depot. The neighborhood boys would fish, crab, and even swim in Nu‘uanu Stream, a pastime illustrated on her map by two stick figures with fishing poles on the bank of the Stream on the right side on the map.

The majority of family businesses on her block are Japanese-owned, but the trades represented are “a melting pot of occupations” – barbershops; several restaurants, some of which serve liquor; pool halls; theaters; grocery and appliance stores; a taxi stand; a Japanese candy store; a general store; shoe store; a camera shop; a jewelry shop; a dressmaker; a magazine center; a photographer’s studio; a dentist’s office; and “a travel service (Dad’s business).” Just across ‘A‘ala Street and fronting what she’s labeled “tenement homes” are a dancehall, grocery, poolhalls, a liquor store, a café, a bar, and a chop suey place – businesses owned by part-Hawaiians, Chinese, and Filipinos.

Across the Park on Beretania Street she has inked in on the map “Japanese stores,” although she writes that one of the stores is owned by a Chinese. Behind these stores is the Market Place, “cosmopolitan” because of the range of the merchandise. She makes note that ethnicities have their occupational niches; for example, Filipinos own and operate barbershops and pool halls.

The Writer

At some point, sociology faculty began using codes rather than writers’ names on the papers. What we do learn from #2095’s paper is that she is female, a U.S. citizen, Okinawan and her father’s occupation. The map tells us where she lives.

Content as a youngster to play with neighborhood kids and to accept ‘A‘ala for what it was, the writer has come to feel somewhat ashamed of the community. This change began when she left the district school to attend English Standard Schools, Kapālama Elementary in Kalihi and Stevenson Intermediate in Makiki, residential areas of Honolulu. (She makes no mention of her high school.) The writer describes the relationships in ‘A‘ala as “secondary,” focused on their businesses with no opportunity, time, or interest in creating social gatherings. Attending schools beyond her neighborhood, she eventually joined a “clique” of school chums and stopped associating with her ‘A‘ala neighborhood friends.

I am not very proud of my home. After seeing the others’ homes with yards and located in “regular,” quiet, residential areas, I was hesitant in inviting [my friends] over to my house. At our age the phrase “Aala Park” had bad connotations in our minds and so I was ashamed in my friends seeing where I lived. When they learned where I lived, they would ask: “Aren’t you afraid of living around there?” I was embarrassed and tried to cover up my feeling of hurt by laughing, saying: “Of course not; maybe the folks living around there should be afraid of me.” (The “folks” stood for the Filipino men who stood around the corners.).

The paper’s final paragraph begins with a tone of resignation: she has come to accept that where she lives has a bad reputation, that her parents cannot afford to buy a home in a residential neighborhood, and she must continue to live in ‘A‘ala. As if an afterthought, the remainder of the paragraph is handwritten, and she describes the positive aspects of ‘A‘ala with its bustling street life:

The pool halls are always quite full with players and spectators crowding the sidewalk; the barber shops always have the over-grown hair of boys and men to cut; the bars are always welcomed spots of the Filipino and part-Hawaiian laborers after a hard day at work; children with their pennies buy bubble gum and candy; and the grocery stores provide the needed supplies for the three meals of families. The Japanese theaters find their patrons from many communities and the taxis have the opportunity of taking the folks home after the movies. … Activity is always in the air around Aala and so the day seems to move rapidly. … The market place and [bus] transfer points help to bring people from different districts to this area. … The leeward buses and leeward taxis that are nearby on Beretania street bring workers and students who commute from Pearl City and Waipahu.

She tries to accept ‘A‘ala but still longs to live in a residential neighborhood. She believes that where one lives not only is a reflection on oneself but of oneself.

RASRL Context

The faculty for this Sociology 151 course asked students to complete two papers during the semester, the first about the writer’s family and the final on the writer’s neighborhood. In #2095’s paper “My Parents” (not in this exhibit) she shares that her father emigrated from Okinawa to Hawai‘i with his family in 1920, hoping to obtain an education but was forced to leave school to support his older brother through college. The writer’s mother was born in Hawai‘i but her family moved to Okinawa, then returned before she could complete her high school education. The writer’s parents married in 1929 and had four children. The writer was the third born.

Typical of many RASRL writers, #2095 focuses on the importance of education in her family. In part, this is due to the nature of the assignments about family and self that either implicitly or explicitly asked students to share their attitudes about attending college and their future career goals. But in this case, education in her family is so highly valued that her parents have sent her to English Standard Schools and UH. Although she is female, her father insisted she attend college, a paternal attitude that often isn’t the case for other RASRL writers.

Today, I am at the University mainly because of Dad’s stubborn wish that all of his children receive a college education. During high school, I had planned to become a secretary or teacher, the former being the first choice. I had planned to go to business school for my training. I didn’t think it was necessary for me to go to the University and spend another five years when I could be out in the business world after two years of further studies. Dad and I often got into a heated argument on this subject and both of us tried to alter the other’s views. However, all of my persuading was in vain, as you can see. Today, as I am writing this paper, I am thankful that Dad did not budge from his ideas, for I find that there is truth in Dad’s statement that the university offers many things that are not found in the business world besides preparing one for his vocation. He has also helped me to decide definitely on my career and I find that each day my desire to become a teacher is deepening.

The tension that pursuing higher education creates is frequently mentioned by RASRL writers. Education is a pathway to upward social and economic mobility, but it also can create a gap between the student and her family. While this writer has high praise for her parents and the sacrifices they made for her and her siblings, she also states that where they live is no place to raise kids. The image she wishes to have of herself is at odds with where she lives as she has come in contact with girls “from Koko Head to Kalihi Valley,” peers who only know what they read in the papers (or likely hear from their families) about ‘A‘ala.

Social Historical Context

This urban study vividly describes the excitement of living in a densely populated area of postwar Honolulu, and introduces us to a family who operates a travel service that requires the father to lead tours to Japan and Okinawa.

As in many RASRL papers, what is left unsaid is often of equal or even greater interest than what we learn from the writers. In this case, we wondered about the resumption of travel to Japan and the Orient after World War II.

In a Time article (April 9, 1956, vol. 67,issue 15, pp. 88+) more Americans than ever were traveling abroad, and the Far East was finally opening up:

For the first time since World War II, the South Sea Islands will be easily available to tourists. In July Australia’s South Pacific Airlines will start twice-weekly flights from Honolulu to Papeete. By October two new Matson liners will be plying the San Francisco-Sydney run, with stops at Tahiti, Samoa and the Fijis.

The 1955 issues of Paradise of the Pacific are full of travel advertisements.

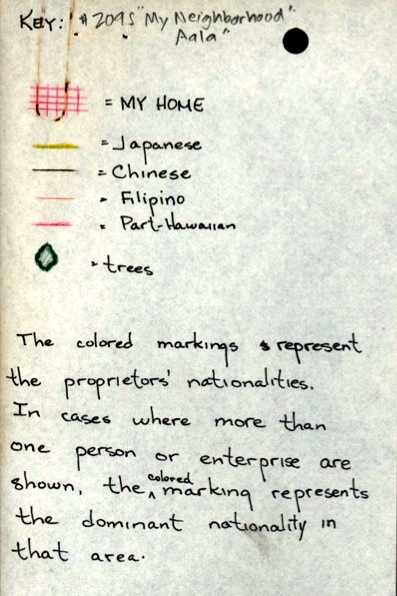

Polk’s Directory of the City and County of Honolulu 1955 lists nearly forty travel agencies operating in Honolulu.  Two are located on King Street, the ‘Ewa side of River Street where #2095’s family lived. Airways Travel Agency at 420 N. King is owned by Walter F.Y. and Mrs. Genevieve H. Liu. Komatsuya Travel Agency at 491 N. King is owned by Ichiro Sato, agents for American President Lines, Pan-American World Airways, United Air Lines, Northwest Airlines, Japan Airlines, Hawaiian Airlines, TPA Aloha Airlines, American Express Co.

Two are located on King Street, the ‘Ewa side of River Street where #2095’s family lived. Airways Travel Agency at 420 N. King is owned by Walter F.Y. and Mrs. Genevieve H. Liu. Komatsuya Travel Agency at 491 N. King is owned by Ichiro Sato, agents for American President Lines, Pan-American World Airways, United Air Lines, Northwest Airlines, Japan Airlines, Hawaiian Airlines, TPA Aloha Airlines, American Express Co.

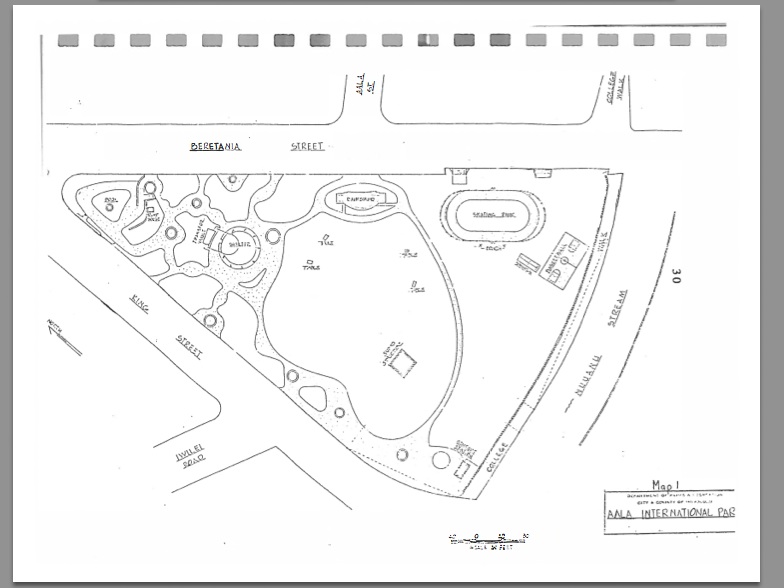

The structures in ‘A‘ala Triangle Park that #2095 drew and described were razed in 1963, a victim of urban renewal. In 1971, the Park was renamed and rededicated as ‘A‘ala International Park with the intent of creating a staging area for a variety of ethnic festivals and celebrations that never quite happened. In 1990 the City of Honolulu contacted the Hawaii Ecumenical Housing Corp. to operate a tent shelter at ‘A‘ala called, appropriately, “tent park.” The first families moved into tent park in May 1990 (Nancy H. Jordan, More Than Just a Bed for the Night: An Ethnography on the Homeless of A’ala Park, Senior Honors Thesis, University of Hawaii, August 1991). Jordan’s thesis includes two maps. The first is a somewhat altered version of #2095’s that shows the Park interrupting the connection of of ‘A‘ala Street to King and the absence of homes and tenements, the Nippon Theater, and a score of businesses, including #2095’s family travel business.

The second map is pertinent to Jordan’s ethnography of the homeless:

In less than ten years, #2095 and her family no longer had a travel business to live above on King Street. The neighborhood became a differently famous ‘A‘ala.