The Paper: “The Ecological Study of the Community: The Keaau Village (Olaa),” 1937

The Writer: C.T.

Location in RASRL: Box A-5

Seven Maps and a Paper

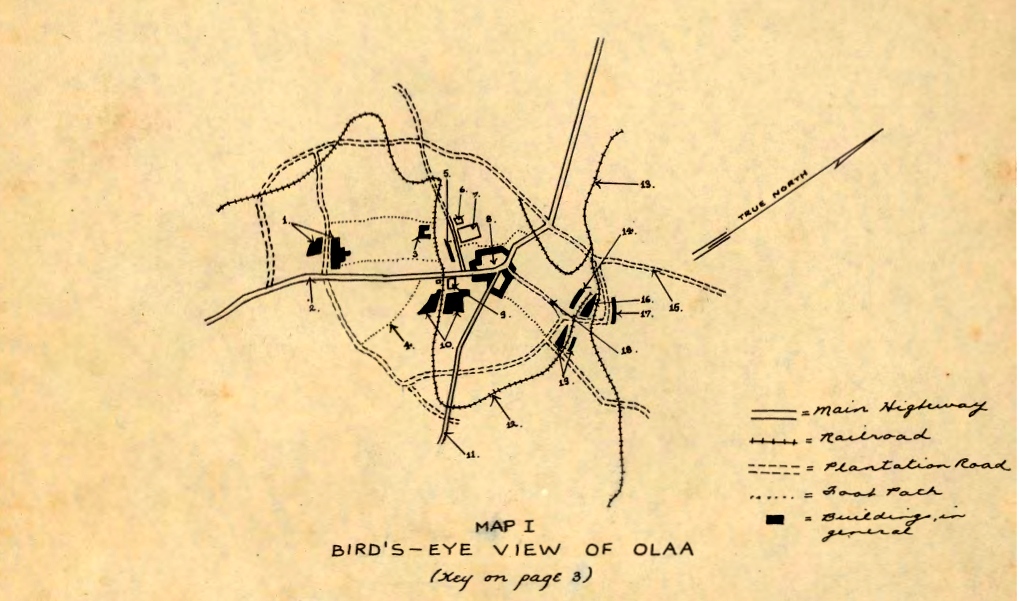

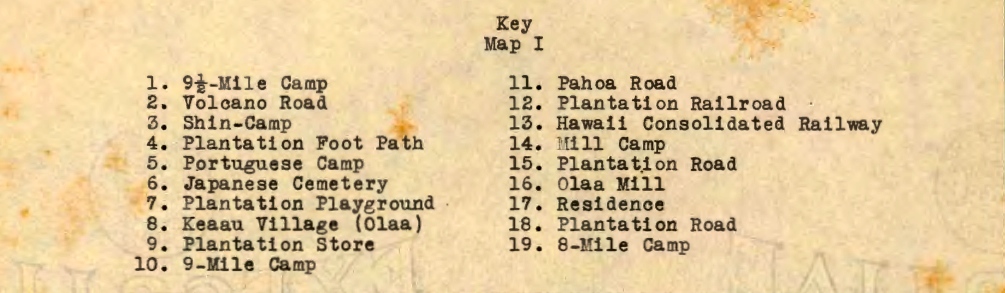

Written for an introductory sociology class, C.T.’s paper is an “ecological study” of Kea‘au village, which was commonly known as Ōla’a village. The village is located about eight miles south of Hilo. What makes C.T.’s work exceptional is the number of maps – seven in all – with their keys – and the exquisitely rendered details they provide. The first map offers a “bird’s eye view” that highlights Kea’au’s major landmarks and transportation network:

The main plantation buildings and structures are in proximity to the village, as well as roads, footpaths, and railroad lines that service both the plantation and village. Although the focus of the paper is on the village, C.T. devotes the first three maps and half the paper’s narrative to the entire plantation-village complex.

Because of the plantation camp’s system of roads and footpaths, workers had easy access to the village. The writer also notes, with apparent pride, the centrality of the village: “It is interesting to note in Map I that the village enjoys a central position. The mill occupies a secondary position in the scheme of the Olaa community.”

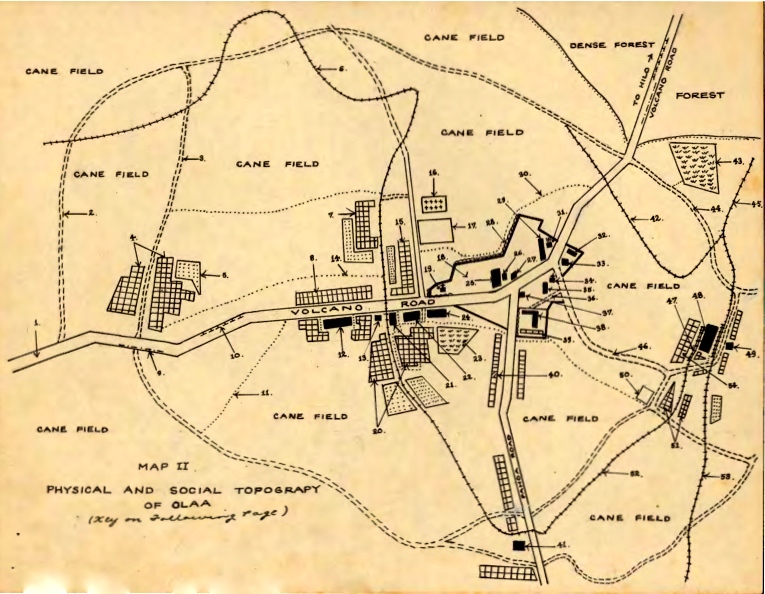

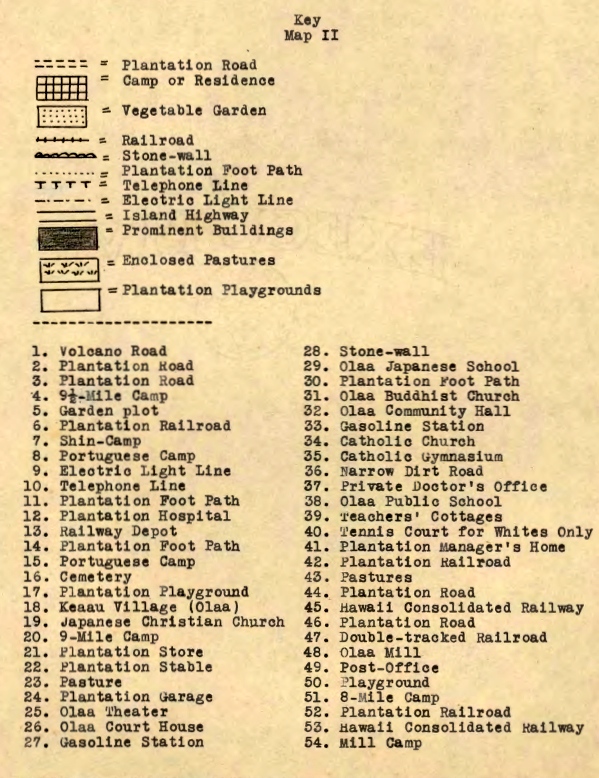

As its title suggests, this map shows both the physical and social attributes of the area (forest, cane fields, pastures, gardens), residences (worker camps, plantation manager’s house, teacher’s cottages), plantation structures (mill, store, cemetery), and some of the key village structures (theater, court house, churches).

In this map, the integration and interconnectedness of the plantation is evident. The plantation-village has a “hub and spoke” layout, in which the village’s school (38 on the map), plantation hospital (12), and store (21) are at the hub. The roads, railroad, and footpaths are the spokes out to the cane fields and mill (48). The worker camps (4, 7, 8, 15, 20, 51, 54) are spread out between the village and the cane fields.

An outer plantation road, like a wheel, encircles the plantation, cuts through all the fields, and runs adjacent to the plantation manager’s house (41) and the mill. A tennis court (40) on Pāhoa Road is marked “for Whites Only.”

While the grade of the land is not shown on this map, C.T. does indicate that the plantation has no prominent natural features, such as rivers and ridges, except for a hill upon which the cemetery sits (16). However, the map does indicate a forest area outside of the plantation-village area towards Hilo.

It is important to note that the village is connected not only to the plantation by its roads and footpaths, but also to the entire Puna district and beyond; it is “ideally situated at the junction of the Volcano Road and the Pāhoa Road.” (See Volcano Road to Hilo at the top right on Map II.)

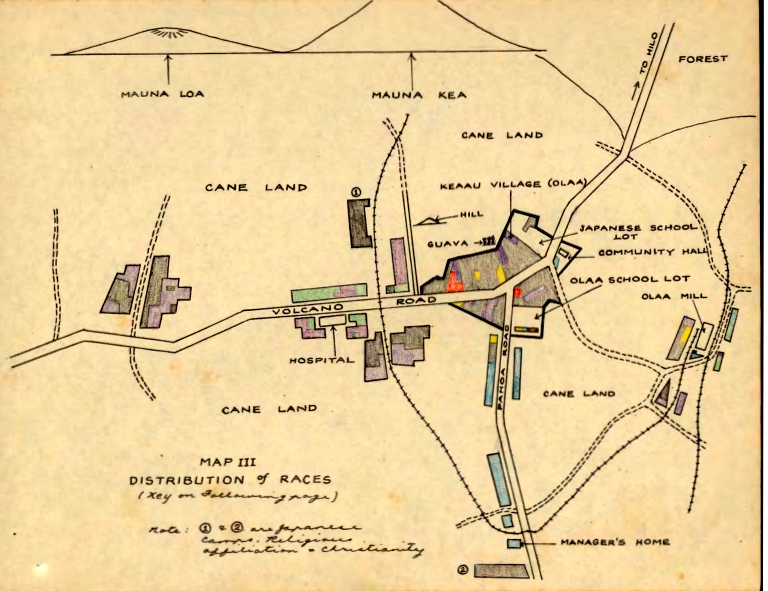

As in all RASRL community studies, locating the placement of ethnic groups in a community is important. In this third map, C.T. offers a delicately colored map of the “distribution of races”: Japanese – grey; Filipino – violet; Portuguese – green; Puerto Rican – purple; Chinese – red; Hawaiian – yellow; and Haole – blue.

As evident on the map, Japanese and Filipinos are the largest groups and occupy most of the camps, followed by the Portuguese and Puerto Ricans. The Haole residences are clustered south along Pāhoa Road, including the manager’s house and a row of residences on either side of the road. The “Whites Only” tennis court (Map II, 40) is an apparent dividing line, separating the Haole from the Japanese and Hawaiian residences.

C.T. describes the different ethnic groups on the plantation and in the village not only by socioeconomic status, but also by a range of demographics (family size) and behavior (church attendance, interracial marriage, and segregated residences).

The Japanese work at field jobs as well as ones in stores and the mill, with the second-generation Japanese having “good jobs.” In the village, the Japanese have the largest families, which the writer reports as having five children per family, who “comprise the play groups and gangs.”

The Filipinos, who are mainly single, work in the field and their socioeconomic status is “low” with “vice, juvenile delinquency, and crime” common among them. Although Catholic, they often do not attend church services.

The Portuguese are “conservative” and the “least mobile” because many have not left the plantation since they immigrated. The Puerto Ricans settle near and sometimes intermarry with the Portuguese.

The Haole represent the “upper crust” of the plantation community, holding the best jobs, and living apart from everyone else.

The Chinese and Hawaiians are small or “insignificant” in number: three Chinese families, who live in the village and operate stores, and the “only important Hawaiian” is the village sheriff. However, the “Distribution of Races” map indicates a Hawaiian teacher’s cottage and some Hawaiian residents in the camp.

The writer concludes that different ethnic groups segregate themselves because of mutual support. Like many RASRL writers, he predicts a future where racial prejudice will be overcome as a result of the “mixing of groups.” He also states that the socioeconomic status of the immigrants will improve as they “migrate” to better jobs, and their US born children will be the most “mobile.”

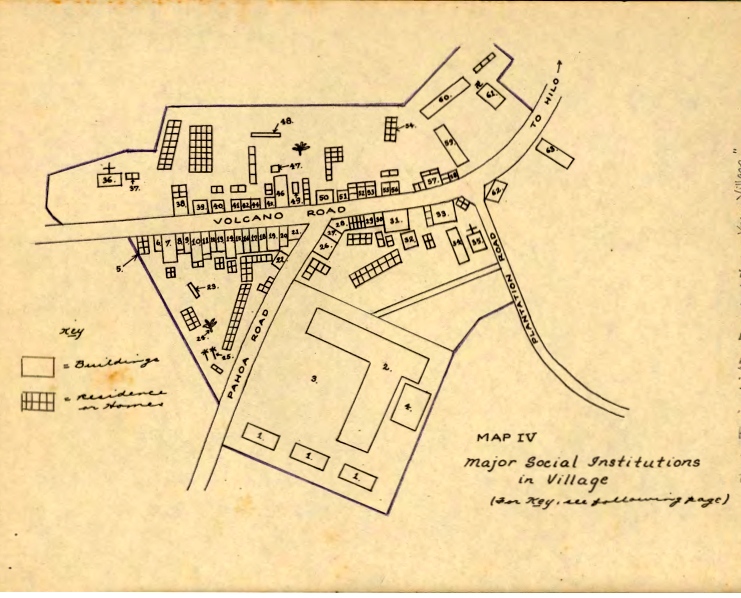

Of the several maps offered here, this map – “Major Social Institutions in Village” – brims with details and clearly illustrates the economic condition of the village in the late 1930s. Although the writer asserts that trade is still at the elementary stage and the village remains dependent on the plantation, what he describes is a growing and bustling community.

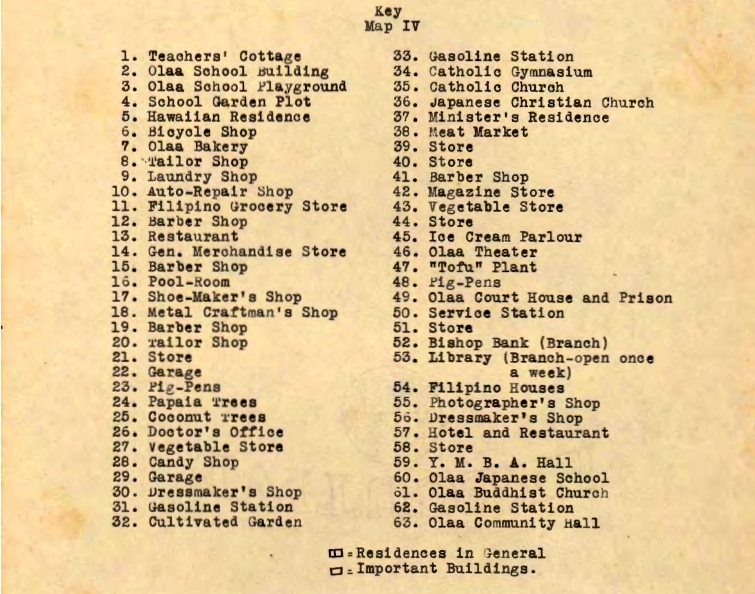

The map key lists sixty-three “institutions” in the village, including central government and community services functions: the courthouse and prison (number 49), library (53), school (2) and community hall (63), as well as a branch office of a bank (52) and a doctor’s office (26).

Three major religions and their affiliated structures occupy large areas in the village and are spaced out in the lower, middle, and upper parts of the village: a Buddhist temple (61), with a connected Japanese language school (60) and social/club hall (“Y.M.B.A.”, 59); a Catholic church (35) and gymnasium (34); and a Japanese Christian Church (36).

Because of the village’s crossroads location, there are a number of shops providing services to cars: four service stations (31, 33, 50, 62) and three auto repair shops or garages (10, 22,29), located mainly around the Pāhoa Road-Volcano Road junction.

Shops that served the residents of both the village and plantation are many: two vegetable stores (27, 43), a meat market (38), a tofu plant (47), a general merchandise store (14), and a Filipino grocery store (11). Personal services, some with two or more shops per trade, are well represented: three barbershops, although the writer says there are five (12, 15, 41), two dressmakers (30, 56), and two tailors (8, 20), as well as a laundry service (9) and bicycle shop (6).

Some village shops also served residents beyond the Ōla‘a plantation-village complex. The bakery (7) made regular deliveries of bread and other baked goods to residents and establishments in Pāhoa and points south of the village (Personal interview, Hisao Okamoto, former Ōla‘a resident and son of the village’s bakeshop owner, December 20, 2016).

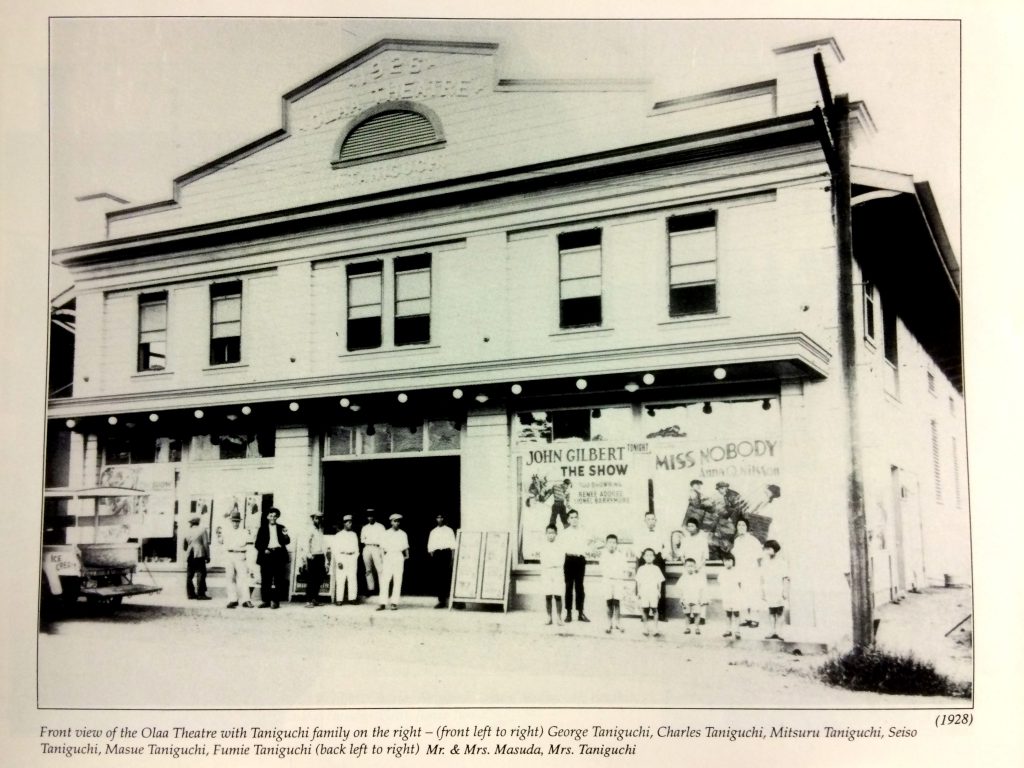

Finally, there are leisure and entertainment venues: a theatre (46), hotel and restaurants (57, 13), candy (28) and ice cream (45) shops, a bakery (7), a magazine shop (42), and a photography studio (55). While not on the map, the writer notes that there is a poolroom in the village.

He notes that there seems to be a building boom:

There are indications that new buildings will replace the old ones. A new Japanese Buddhist Church is, at present, under construction. It will replace the 30 years old wooden structure. The dilapidated camp houses are being either remodeled or replaced with new ones. The Olaa Theatre has already undergone several reinnovations [sic]. The gasoline station (Map IV, 62) was only recently constructed.

The village is also a gathering place for both the plantation workers and village residents. The three churches hold Sunday services and are “centers for gossip.” For church members and social clubs, the Catholic Church has a gym and the Buddhist Church, the YMBA (Young Men’s Buddhist Association) and YWBA (Young Women’s Buddhist Association). The poolroom, school playground, community hall dances, and Boy Scout meetings provide opportunity for children and young adults to gather for informal and formal activities.

It is interesting to note that the row of teachers’ cottages (Map IV, 1, lower center; Map III, “Olaa School Lot,” middle) challenges an otherwise highly segregated community. The cottages are the village’s most integrated residential area with Hawaiian, White, Japanese, and Chinese residents. Akinori Imai, who was about ten years younger than C.T., indicated in his Ōla‘a memoirs the names of some of his teachers at Ōla‘a School: Mrs. Blackerdar (“whose roots were in Norway”), Miss Brown, Miss Imamura, Miss Kaulukukui, Mrs. Koga, Mr. Lum, Mrs. Mehau, Mr. Nahiwa, Miss Nye, Miss Okubo, Mrs. Shaffer, Miss Tenn, Mr. Watanabe, and Mrs. Watt (“Our Nostalgic Heritage: Growing Up in a place Once Called Ola‘a,” pp. 159-164). Imai does not mention which teachers lived in the teachers’ cottages, but at least one did not, Mrs. Watt, the plantation manager’s wife.

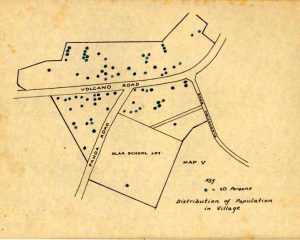

According to Map V, the village population is about 800 people and evenly distributed among the three quadrants of the village. The larger share of the population lives along the roads, either behind or above shops and businesses.

According to Map V, the village population is about 800 people and evenly distributed among the three quadrants of the village. The larger share of the population lives along the roads, either behind or above shops and businesses.

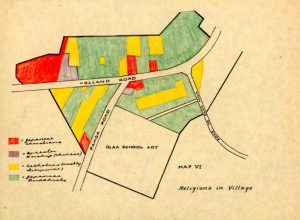

In Map VI, C.T. uses vibrant colors to identify the  location of the residents and buildings of the three major ethnic-based religious groups of the population: Japanese Buddhists; Catholics, whom the writer notes are mainly Filipino; and Japanese Christians. “Ancestor Worship,” which the writer identifies as Chinese, appears to be a small segment of the plantation-village population and does not have a building in which it is housed.

location of the residents and buildings of the three major ethnic-based religious groups of the population: Japanese Buddhists; Catholics, whom the writer notes are mainly Filipino; and Japanese Christians. “Ancestor Worship,” which the writer identifies as Chinese, appears to be a small segment of the plantation-village population and does not have a building in which it is housed.

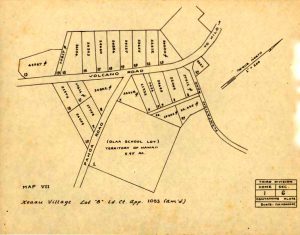

“Keaau Village Lot “B” Ld. Ct. App. 1053 (Am’d),” Map VII, which the writer says he obtained from the Honolulu Survey Bureau, shows the tax assessment parcels in the village. In each parcel on the map, the square footage or acreage of the parcel is indicated in the middle of the parcel and, according to the writer, the “key numbers” at the lower left of the parcel (and underlined) reference tax valuations for each parcel. Unfortunately, the names of the lessees and the valuation of the parcels are not offered either in a key or the paper. However, in his paper, C.T. does indicate that the village land is owned by one person.

“Keaau Village Lot “B” Ld. Ct. App. 1053 (Am’d),” Map VII, which the writer says he obtained from the Honolulu Survey Bureau, shows the tax assessment parcels in the village. In each parcel on the map, the square footage or acreage of the parcel is indicated in the middle of the parcel and, according to the writer, the “key numbers” at the lower left of the parcel (and underlined) reference tax valuations for each parcel. Unfortunately, the names of the lessees and the valuation of the parcels are not offered either in a key or the paper. However, in his paper, C.T. does indicate that the village land is owned by one person.

Social Historical Context

The writer describes Kea‘au village as a vibrant and prospering gathering place, literally drawing the plantation workers down the roads and paths to its wide range of services, stores, and entertainment establishments, as well as schools and churches. The village offers the workers a concrete vision of life other than that on the plantation: “Migrations to a better field of occupation are constantly going on. In this respect the second generation of immigrants seems to be the most mobile.”

Plantation management, however, was actively working against this out-migration from the plantation. A.J. Watt, manager of Olaa Sugar Company from 1922 to 1938, was considered liberal for his efforts in improving employee housing and providing community resources. Others would describe these efforts as paternalistic. However, Watt, like other plantation managers, was under pressure to recruit and retain labor, especially the US born children of immigrant laborers or “citizen employees,” as the Hawaii Sugar Planters’ Association (HSPA) called them. The HSPA was an organization of Hawai‘i sugarcane plantation owners founded in 1895 that promoted the development of the sugar industry. Through the HSPA, the owners shared information of mutual benefit, from scientific research and plantation management practices to controlling labor to maximize economic gain. The HSPA facilitated the recruitment of international labor, lobbied the US for immigration and trade legislation favorable to the industry in Hawai‘i, and was a powerful influence on Hawaii’s politics and economy prior to World War II.

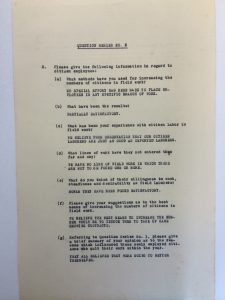

In a 1932 HSPA Industrial Committee survey of plantation managers, Watt was asked for quantitative and qualitative data on newly employed citizen-employees in his company. The HSPA wanted to find out who the workers were, why they were quitting, and how managers were working with the public schools to recruit them (“H.S.P.A. – Industrial Relations Committee, Questions Series 1-3, Olaa Sugar Company Limited,” PSC [41/17] Industrial Service Department 1933, HSPA Plantation Archives, UHM Hamilton Library).

In Question Series 1, Watt’s response to the survey indicates that these new citizen-employees are primarily the sons of Japanese immigrant employees, raised on the plantation, educated through the eighth grade, between the ages of 15 and 23, unmarried, and field workers without long-term contracts. The overall attrition of newly hired citizen-employees was reported at about 14 percent (sixteen quit and ninety-nine remained out of 115), with ten of the sixteen leaving to work in Hilo. Citizen-employees who were more likely to leave the plantation to seek work elsewhere were older, married, and had more education.

In Question Series 1, Watt’s response to the survey indicates that these new citizen-employees are primarily the sons of Japanese immigrant employees, raised on the plantation, educated through the eighth grade, between the ages of 15 and 23, unmarried, and field workers without long-term contracts. The overall attrition of newly hired citizen-employees was reported at about 14 percent (sixteen quit and ninety-nine remained out of 115), with ten of the sixteen leaving to work in Hilo. Citizen-employees who were more likely to leave the plantation to seek work elsewhere were older, married, and had more education.

Question Series 2 items clearly show that the HSPA wanted citizen-employees to become field  workers. The survey asks managers for suggestions to increase the number of citizen-employees in the field. Watt’s response was to “induce” them to take cane growing contracts, perhaps through better terms and acknowledging their desire for upward mobility. In fact, Watt’s response to the last item, which asks why citizen-employees are quitting, almost mirrors the writer’s conclusion in his ecological study: “They all believed they were going to better themselves.”

workers. The survey asks managers for suggestions to increase the number of citizen-employees in the field. Watt’s response was to “induce” them to take cane growing contracts, perhaps through better terms and acknowledging their desire for upward mobility. In fact, Watt’s response to the last item, which asks why citizen-employees are quitting, almost mirrors the writer’s conclusion in his ecological study: “They all believed they were going to better themselves.”

The HSPA saw the government schools as recruiting grounds for potential citizen-employees for the plantations and, based on Questions Series 3, approached this in a systematic way. The HSPA asked for data on the distance of the schools from the plantation, grade levels of the schools, and annual number of students graduating from each school. Managers were also asked whether there was a “vocational agricultural class” at the local school, the number of students in that class, the class’s effectiveness, and the connection between the plantation’s work and fieldwork done for the class.

The HSPA saw the government schools as recruiting grounds for potential citizen-employees for the plantations and, based on Questions Series 3, approached this in a systematic way. The HSPA asked for data on the distance of the schools from the plantation, grade levels of the schools, and annual number of students graduating from each school. Managers were also asked whether there was a “vocational agricultural class” at the local school, the number of students in that class, the class’s effectiveness, and the connection between the plantation’s work and fieldwork done for the class.

It is interesting to note that Ōla‘a School had sixty graduating students, the largest number among all the schools, but only five students in the agricultural class. Pāhoa, on the other hand, had twenty graduating students but with twenty-one students in the agricultural class. The relatively low number of students in the agricultural class at Ōla‘a School may have been due to the lack of interest in working on the plantation by the children of the Kea‘au village merchants. These citizen-children of immigrants may have been looking toward Hilo and life beyond the plantation as their future.

In addition, across the Territory, the curriculum of the public education school system emphasized English, literature, and American history with the aim of making the children of immigrants good American citizens. This focus was inherently at odds with the vocational agricultural educational path that the HSPA wanted citizen-children of immigrants to follow.

Ōla‘a School’s curriculum emphasized Western culture and the faculty embraced it. According to one resident who attended Ōla‘a School in the 1930s and 40s:

Speaking of entertainment, the school faculty was quite a talented group. The faculty members once took part in a Gilbert & Sullivan performance of H.M.S. Pinafore at the Ola’a Theatre. It was indeed a well-executed production full of gusto and enthusiasm (Imai, p. 160).

I had Miss Nye, a newly [sic] graduate of [the] Boston Conservatory of Music, on her first teaching assignment, at Ola‘a School during my 7th grade year. … When we were in the midst of the war, Miss Nye gathered the entire student body at Ola‘a Theater for community singing of patriotic songs. … She even composed a song, “The Victory Corps Song” for us students who worked on the sugar cane fields to fill the labor shortage, on the plantation (pp. 163-164).

Also a teacher at Ōla’a School, Watt’s wife apparently was dedicated to educating the children of her husband’s immigrant workers.

Mrs. Martha Watt, wife of the plantation field supervisor, was our 9th grade English literature teacher. We studied literary works such as Ivanhoe, Courtship of Miles Standish, Longfellow’s Song of Hiawatha, and Victor Hugo’s Les Miserables with her. Besides all of this, she helped me in overcoming a big stumbling block in my life. Oftentimes, living and understanding two cultures could cause some difficulties. In my case, even as a 9th grader, I had difficulty responding to a negatively posed question (p. 164).

One can only speculate if Watt’s wife, working with the children of his employees, influenced the development of Watt’s views on employee welfare and openness to having citizen-employees work at non-field jobs. But Watt’s personal ties with Ōla‘a School may have helped him smooth the waters in recruiting future workers from area schools.

The HSPA was very concerned about the relationship managers had with the schools and devoted the last three items in Question Series 3 to this: could managers work with the schools in placing students in plantation jobs; what was the schools’ attitude toward the manager’s “efforts to increase the number of citizen employees;” and how cooperative were the schools “in matters affecting the plantation and its employees.” This line of questioning implied that managers may have had problems with school administration and teachers as the managers tried to establish and boost enrollment in the agricultural classes.

In addition to the recruitment tactics described by Watt in the HSPA survey, he and subsequent managers provided summer employment for children of plantation workers as a way to extend vocational training outside of the agricultural classes in the schools. William L.S. Williams, the manager who succeeded Watt in 1938, wrote a letter to AmFac, the company’s agent in Honolulu, in which he reported on the plantation’s efforts to follow federal and Territory child labor laws while employing minors during summer vacation (Letter No. 6696, April 9, 1940. PSC [38/20] Child Labor 1935-1940, HSPA Plantation Archives, UHM Hamilton Library). Williams justified summer employment of plantation children as a way not only to provide another source of revenue for the families and to keep the children “out of mischief” during the summer, but also to offer “training in agriculture work” and “discipline,” which the children would need as future employees.

Even village children were hired to do summer fieldwork on the plantation, perhaps as an effort to encourage these children to work in the fields after graduation (Okamoto interview, September 8, 2016).

The Writer

Born in Honomū, north of Hilo, this RASRL writer and his family at some point moved to Ōla‘a where they operated a movie theatre (“Olaa Kurtistown 1996 Oldtimers Reunion, July 12-13, 1996”). Although the son of a merchant in the village, C.T. likely gained his knowledge of plantation life through contact with workers who frequented the theater and other establishments in the village.

In the 1939 issue of UH’s yearbook (Ka Palapala), the year he graduated, C.T. was listed as a “pre-legal” student. He was also a member of ROTC and Hakuba Kai, a Japanese fraternity. After graduation, C.T. attended law school and was listed as a first-year student in the Class of 1940 Harvard Law School Yearbook. According to his obituary, C.T. eventually became a deputy attorney in Honolulu after World War II.

As C.T.’s biography illustrates, the aspirations of mobility, often fulfilled by citizen-children of Japanese immigrants seeking work in higher occupations, were perhaps too strong a force to hold back, as plantation managers turned increasingly to imported labor, primarily Filipinos, during the 1930s. The writer hints at his own personal desire for that ultimate statement of assimilation into Western society – land ownership, the badge of legitimacy for upwardly mobile immigrants.

Home ownership is very rare in the plantation. In the village, Mr. X leases out land. He is indifferent to any offer to purchase his land.

“Mr. X” is William Herbert Shipman (1854-1943), son of missionaries and husband of Mary (Mele) Elizabeth Kahiwaaiali‘i Johnson, grandniece of Isaac Davis and granddaughter of Kauwe, a member of the Hawaiian ali‘i on Maui. Shipman purchased the Kea‘au ahupua‘a from the King Lunalilo Estate in 1881, and then joined B. F. Dillingham and other investors in starting the Olaa Sugar Company in 1899. Bold for their times, these owners envisioned this company, later renamed the Puna Sugar Company, as a new type of plantation, almost an experiment in American enterprise, in which the plantation would consist of contract laborers who would own or lease plots of cane land, and a plantation that would mill and market the sugar products. Immigrant laborers did have contracts to lease plots, but land ownership came more slowly.

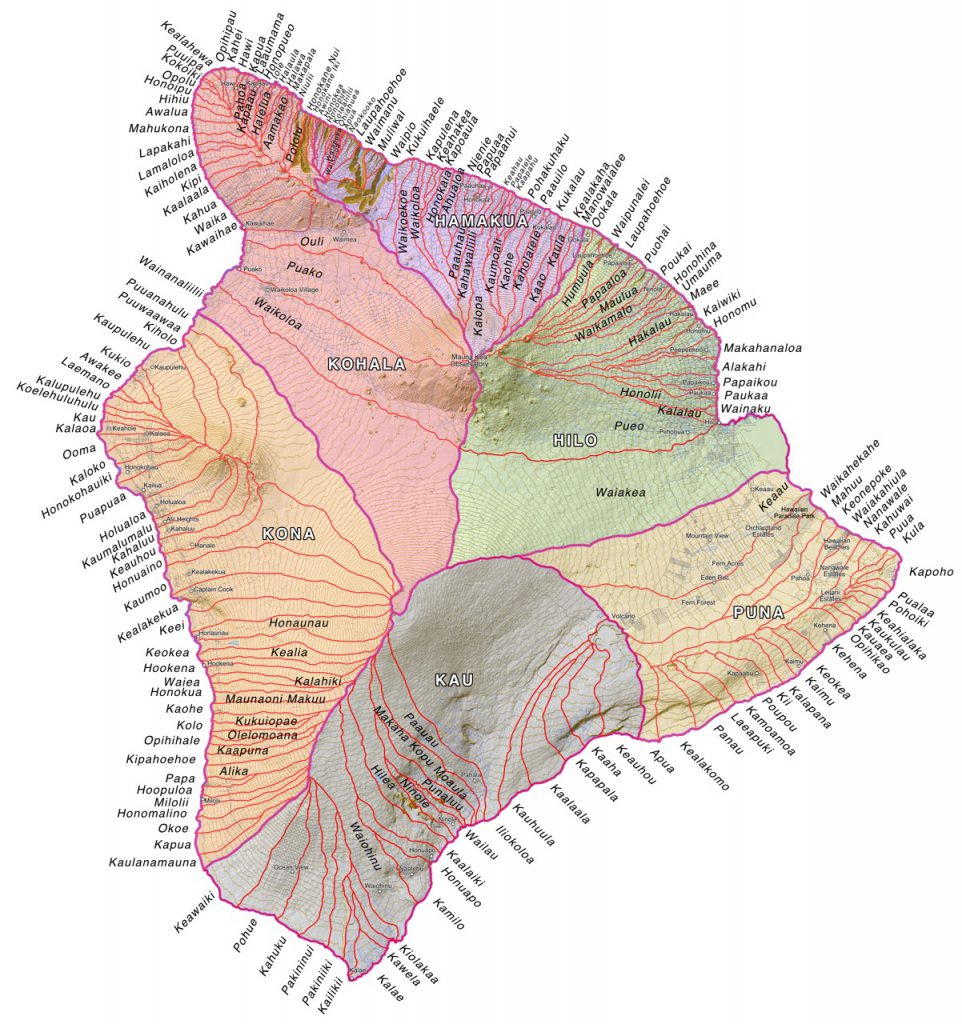

Hawai‘i moku map from IslandBreath.org

Ironically, almost 100 years later, when the Puna Sugar Company closed in 1984, AmFac, which by this time had 100 percent interest in the company, offered each employee four acres of plantation land. As for Kea‘au village, the W.H. Shipman, Ltd. Company still owns much of the land, leasing out parcels to tenants.

Mahalo to Michael Kirk-Kuwaye for his research and write up of this post.