The Paper: “The Moanalua Gardens,” 1939

The Writer: K.N.

Location in RASRL: Lind Student Papers Box 6

The Paper

“The Moanalua Gardens” is a community study but it is unusual in that it does not focus on a neighborhood or town. Moanalua Gardens is a public park located on private land owned by the Damon family. The Garden, which opened in 1924, is in the ahupua‘a of Moanalua just ewa of Honolulu. The property was managed by employees of the Damon family, and K.N.’s paper describes the community of people who lived there.

The paper is brief – only seven typewritten pages – not because the writer felt that the community was unimportant but because it was small and did not allow for extensive analysis. The paper primarily describes the residents of the community using ordinary demographic measures. There are forty families (approximately 193 people), most of them school-aged children or young adolescents. Japanese are the largest ethnic group (33%); there are also Chinese, Scots, and Portuguese employees. The writer uses the traditional racial groupings that distinguished Hawaiians, Caucasian-Hawaiians, and Chinese-Hawaiians as separate groups. Taken together, however, Hawaiians are the second largest group among the employees and residents of the Gardens. Most of the residents are employed by the Damon family as staff to maintain the property or as domestic help for the members of the family who live on the grounds. The only residents of the Gardens who are not employed by the Damon estate are Hawaiians who “have a different residential status.” K.N. does not explain what this means, but only says that they lease areas of the property for $1 a year.

The writer adds class distinctions to his discussion of race saying that “three Scotchmen and their families compose the elite.” K. N. may be referring to Donald MacKinnon whom Samuel Damon hired to oversee the building of Moanalua Gardens. The other two White employees are the nursery foreman and a watchman. The watchman’s family is “…less separate from the rest of the population than the superintendent and the foreman because of the nature of his work and because of his son’s intimacy with the boys of the area.”

The only other Haole living in and around Moanalua Gardens are the Damons who are described as distant land owners, not involved in the day-to-day lives of the residents. “The Damon’s do not seek to place rigid controls over the residents, for they have nothing to gain by doing it.” The residents of the community, however, are acutely aware of the Damons who seemed to exercise passive control over the employees. The writer says the residents were appropriately deferential but are reluctant to upset the family with unruly behavior or in any way “let themselves go.”

The Writer

The RASRL writers, the young men and women who produced the maps and papers that we are analyzing, were ordinary people. We occasionally run across the work of someone who was from a prominent family or went on to gain notoriety as a politician, entertainer, writer, or entrepreneur. But it is more often the case that after leaving school, the writer went on to live an ordinary life as a teacher, a librarian, or an employee of a local business.

This seems to be the case with this writer. He was born in 1918, one of three children. He and his family lived in lower Kalihi, a place K.N. returned to after college and stayed for the rest of his life. Unless he attended a private school (which is unlikely given his father’s work which in 1940 earned him a yearly salary of $2,496), K.N most certainly attended local public schools. Although he was fourteen when Roosevelt high school opened in 1932, it is unlikely that he could have passed the stringent oral entrance exam for Roosevelt that required students speak flawless standard English. It is much more likely that he graduated from McKinley High School in 1935.

Since we know with some certainty when K.N. was born and when he graduated from the University of Hawai‘i (1939), it is clear that he went straight through high school and college with no time off. His family was clearly not wealthy so it is likely that they saved to send him to school or he worked to pay his tuition and fees. While at UH, K.N. was a member of the band, although we don’t know what instrument he played. He was also a member of Hawaii Quill, the campus literary club. Interestingly, in the year he is listed as a member, 1937, he was the only Japanese American male in the group. (According to the 1938 Ka Palapala, the purpose of the group was to “…foster the germ of genius among campus writers…”) When he graduated in 1939, no additional clubs or activities are listed below his name. If he was working his way through school, perhaps contributing to the household expenses for his family, he may not have had time to spare for clubs and social activities.

K.N. enlisted in the army only a month before the bombing of Pearl Harbor and served with the storied 442nd Battalion for the duration of the war. K.N. was a social science major and after the war he worked for the Department of Public Welfare. He later moved to the Hawai‘i State Library where he worked until he retired some time in the late 1970s. K.N. died in 1994 and was survived by his two sisters.

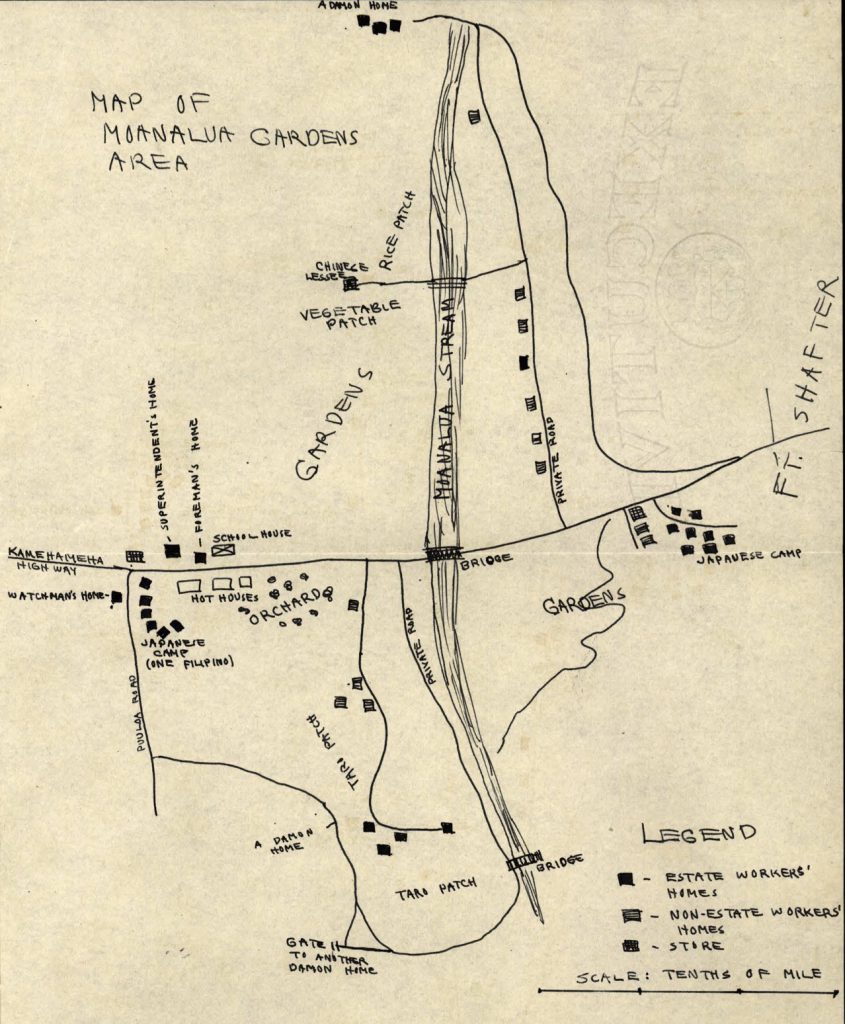

The Map

K.N.’s paper includes one map, a simple pen and ink sketch that shows a section of the property. (If his map is true to scale, this is an area of less than a square mile.) It is not particularly well drawn nor is it precise. Many of the structures are not labeled and the labels themselves are indistinct and almost unreadable. There are few buildings; three small clusters of homes near the center of the Gardens. The homes of the members of the Damon family are indicated at the top of the map, further into the valley and away from Kamehameha Highway. A gate and a private road also mark the boundaries between public and privates space.

Most of the buildings are the homes of the employees and residents. There is at least one store and a schoolhouse but the paper does not provide any detail about them. The fact that there are no churches or other businesses is an indication of how unusual this community is when compared to other community studies in the RASRL collection. The only other buildings depicted are the hot houses. The homes of non-estate workers are spread throughout the Gardens but, as K. N. notes in his paper, most of the workers are clustered together very near to the hot houses and the orchard. The map shows the location of gardens on either side of Moanalua Stream. These are, ostensibly, the formally maintained gardens that were open to the public.

The most prominent features of the map are the natural elements: the Garden itself, Moanalua Stream, and a large lo‘i. There is also a vegetable garden and rice paddy located higher up in the Valley, land leased to a Chinese farmer. This bucolic scene distinguishes this map. Most of the locations described in the RASRL collection are in urban neighborhoods. They show crowded housing with few natural spaces, save a park or the ocean and mountains on the borders. Even the maps that show rural plantation communities rarely depict the environment as anything other than utilitarian. But Moanalua is a large open space. The houses occupy only a tiny portion of the grounds. Whereas on a map of a plantation town those same houses would be crowded next to a cane field, the local business district or the railroad tracks; in Moanalua, the workers live near the orchard and hot houses, the only “businesses” that support the community. The paper makes no mention of the most well-known feature of the Gardens, a large monkey pod tree with an umbrella shaped canopy. It isn’t clear whether the tree is outside the boundaries of the map or he simply didn’t consider it important enough to draw or discuss.

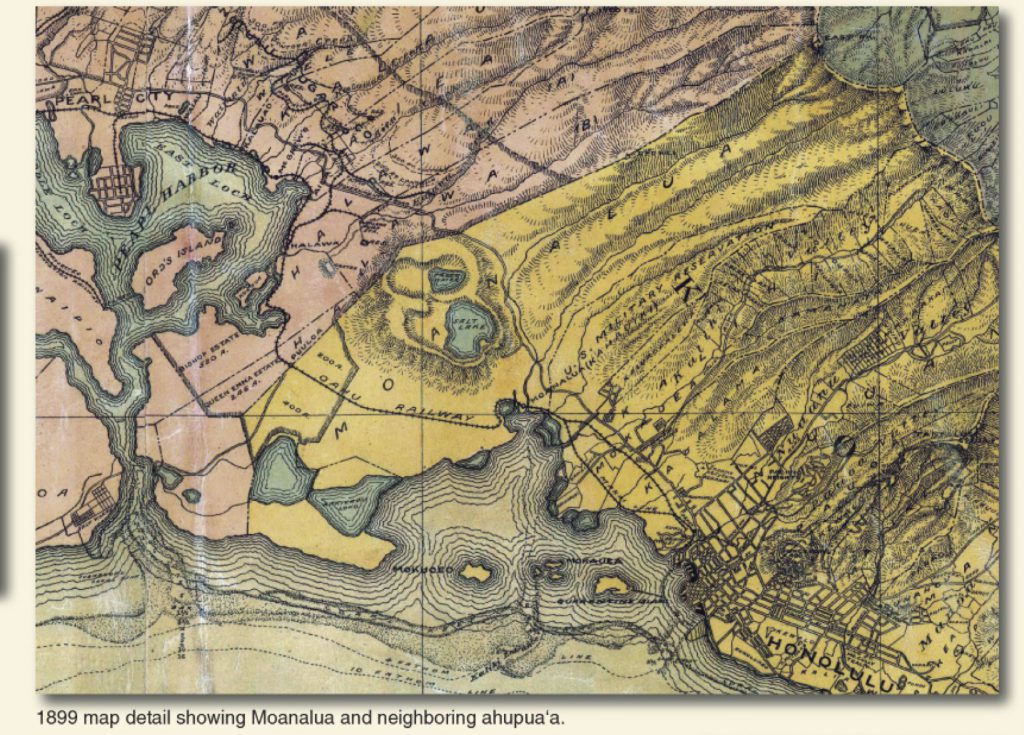

Moanalua and Neighboring Ahupua‘a, 1899 (Source: Moanalua Gardens Foundation)

Historical Social Context

Moanalua Gardens is part of the ahupua‘a of Moanalua. It belonged to the descendants of Lot Kupāiwa (Kamehameha V) and Princess Ruth Ke‘elikolani. Samuel Damon leased part of the land from her to operate a ranch (“He Mo‘olelo ‘Āina: Traditions and Storied Places in the District of ‘Ewa and Moanalua,” Kumu Pono Associates, April 2012, p. 169). When she died in 1883, Ke‘elikonlani left the land to Bernice Pauahi Bishop who in turn bequeathed it to Samuel Damon, her husband’s business partner. According to some sources, Kalākaua was angry that such a large tract of land was given away to a Haole:

Mrs. Bishop had her reasons … and like every other item in her noble will, it has proven to be a wise devise. Had the estate been willed to a Chief or even to the B.P. Bishop Trust it would not have been kept up in the splendid form it is. The income from the rents of the land and fish-ponds are princely, but Mr. Damon spends a large part in maintaining it. Like Caesar’s will, Mrs. Bishop’s has made the populace her heirs, for who does not enjoy the beauty of the valley as much so as if it was his own, and that too without the expense the owning of it would entail? Mr. Damon places no restraint on the public viewing it and using it farther than such as is necessary for the welfare of the grounds and valley (J. W. Girvin, “Moanalua” Hawaiian Gazette August 17, 1906; reprinted in “He Mo‘olelo ‘Āina: Traditions and Storied Places in the District of ‘Ewa and Moanalua,” Kumu Pono Associates, April 2012, pp. 194-95).

Pauahi’s gift of such a large tract of land to Damon is indicative of the relationship between the ali‘i nui and the missionary families. Pauahi and Damon were schoolmates and Damon was Charles Reed Bishop’s business partner. Damon was the executor of Pauahi’s will, which made him one of the first Trustees of the largest single land holding entity in Hawai‘i, the Bishop Estate. The US military commandeered portions of the surrounding areas during World War II, paving the way for further development, most notably the land needed to build the Honolulu International Airport. The Damon Estate dissolved in 2004 and the State of Hawai‘i subsequently acquired thousands of acres.

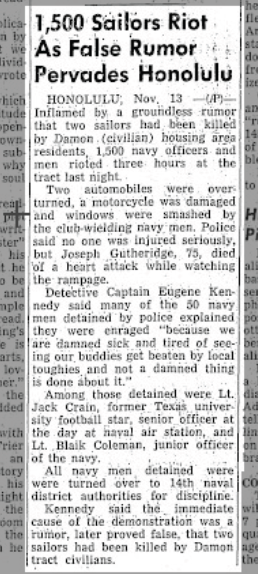

Moanalua Gardens is surrounded by US military installations. K.N.’s map shows Fort Shafter on the Diamond Head side of the Gardens. Fort Shafter, the oldest military base in Hawai‘i, was established in 1907 on Crown Lands, land ceded to the United States after the annexation of Hawai‘i in 1898. During World War II, the Fort’s hospital was expanded into Tripler Army Medical Center, Hawaii’s second (and most visible) “Pink Palace.” Pearl Harbor is not shown on the map, but it is only a few miles away. When this paper was written, the area was experiencing an unprecedented level of development as the US geared up for war in the Pacific. The large number of servicemen and defense workers who crowded into Honolulu before and during the war created tension that sometimes erupted into physical violence. One incident became known as the Damon Tract riot, a melee that took place in November 1945. According to Kelli Nakamura, the riot was “one of the largest post war military uprisings on American soil.” The uprising was, in effect, a race riot that pitted service men against locals. By the end of the war, each group had endured the others’ presence and racial insults. Fights were not uncommon; local “boys” resented servicemen dating “their” women; service personnel relieved some of the tension of being far from home and close to death by abusing locals who were, as far as they were concerned, little better than the foreign enemy or as bad as the most despised racial minorities on the continent (Kelli Nakamura, “A ‘Revenge Bound Orgy’: The Conflict Between Hawai‘i’s Local and Military Culture in the 1945 Damon Tract Riot.” Unpublished paper, N.D., p. 1).

The “Damon Tract” has all but disappeared from Honolulu maps and local memory. The neighborhood, which only existed for a few years beginning in the Depression-era and ending in the late 1950s, was considered by some to be a shanty town. The land was leased from the Damon estate and landlords built cheap housing. Damon Tract was a marginal neighborhood with street names like “T Street,” as if the developers couldn’t be bothered to come up with proper names or ones that would make the neighborhood more appealing.

Damon Tract wasn’t a particularly desirable location, but in 1956 the Damon estate planned to redevelop it. They set about evicting the 4,000 residents but were unprepared for the “hornets nest of protest” they stirred up (George Cooper and Gavan Daws, Land and Power in Hawai‘i, p. 301). The residents protested to the Planning Commission that they were being unfairly treated and that there was no guarantee that they would be able to afford to move back into their homes once re-development began. They complained about not being compensated for the improvements they had made on the property. The estate eventually sold the 233-acre Damon Tract to real estate developers and in a subsequent transaction, the Territory of Hawai‘i bought 67 acres to be used to expand the airport for nearly $5 million.

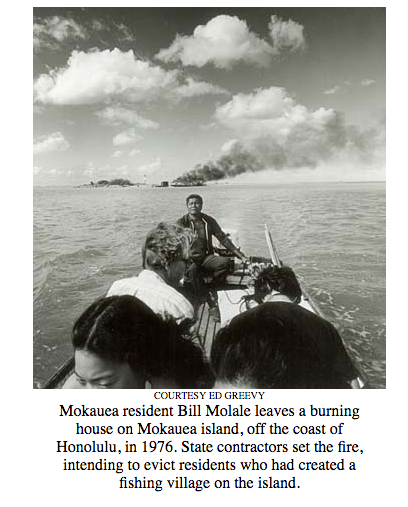

Development threatened another part of the ahupua‘a, the islands and traditional fishing villages in Ke‘ehi Lagoon. The Hawaiian families mentioned in K.N.’s paper were most likely part of a larger Hawaiian community centered around several islands and fishing ponds in Ke‘ehi Lagoon. In a survey and travel guide written by George Bowser in 1880, it was noted that Ke‘elikolani owned the land. According to Nathan Napoka, the ahupua‘a also contained several islands:

Prior to any dredging or land filling three islands existed on the west side of Kalihi Channel. These islands were called Moku‘eo also called Damon Island (sometimes spelled Mokuoe‘o), Mokupilo also called Mokuoniki or Onini Island, and Mokumoa Island. These islands were considered part of the Moanalua land division (Nathan Napoka, “Mokauea Island: A Historical Study.” Historic Preservation Office, Department of Land and Natural Resources, December 1976, p. 1).

Mokauea was one of the last fishing villages in Hawai‘i. In the 1970s, the residents were almost evicted and the island taken over for industrial development. The residents, along with members of “Save Our Surf,” joined forces to save the fishing village from destruction. The island is still occupied and undergoing restoration of its loko i‘a (fish ponds) and other cultural and natural resources.

RASRL Context

The paper, like the map, is only a bare sketch of the small community that lived in Moanalua Gardens in 1939. But it connects past and present in an interesting way, hinting at the lives of Native Hawaiians who still lived relatively traditional lives in an industrial area of Honolulu that was surrounded by military installations. We rarely see Native Hawaiians in the RASRL collection, as actors or subjects, so K.N.’s map provides a glimpse that raises some intriguing questions. For example, K.N. mentions but does not dwell on the Hawaiian community in Moanalua Gardens. Unlike the Japanese who lived in camps, at least some of the Hawaiian residents lived near the lo‘i, which suggests that they were its caretakers or made use of the lo‘i to produce poi for sale. If he was correct, there were thirteen Hawaiian families living in Moanalua Gardens. Since the ahupua‘a had been passed down nearly intact from Kamehameha to Damon, did these families have the same deep ties to the land? Were they retainers of Pauahi? Was there a codicil in her will that allowed them to stay for only $1 a year? How did this more informal arrangement compare with the more structured and infinitely more complicated allocation of lands under the Hawaiian Homestead Act (1920), a program that was established to “rehabilitate” Hawaiians by returning them to the land?

Since a goal of the “Mapping the Territory” exhibit and this site is to raise questions, samples of material from the archive that are incomplete provide a point of entry for further research, and a chance to connect the dots between ourselves and the RASRL writers.