The Paper: “Survey of Kahuku as Plantation Town”

The Writer: M.M.

Location in RASRL: Box A-4

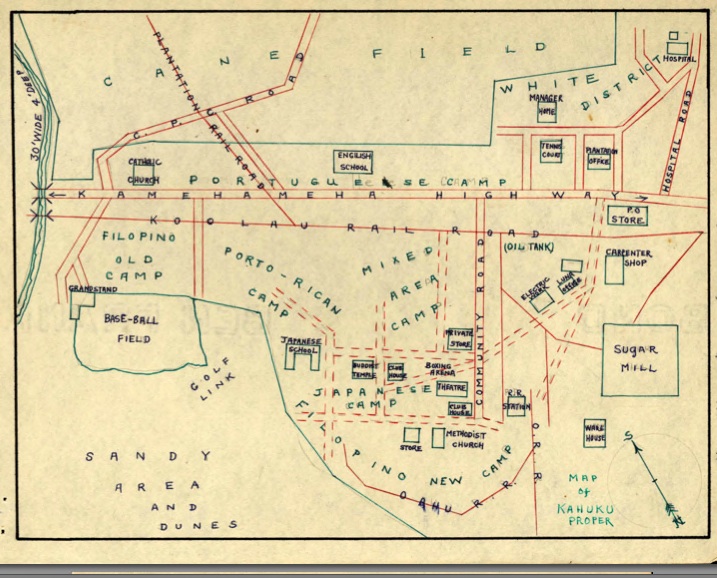

The Map

In many ways, this map was the inspiration for this exhibit. It was found among the community studies papers, a subset of the RASRL Collection. We were drawn to its clarity, its use of color, and small details – the width of the stream, the overlapping lines of the railroad tracks and the streets. The map made us wonder about the writer; the writer made us curious about how it came to be that we were examining the work of a young man who had lived at the beginning of the last century.

The map is beautiful in part because it has stood the test of time. Sandwiched between the other pages of his paper, it resisted some of the deterioration seen in other RASRL papers and maps. The colors are still vibrant and the text is still readable. M.M.’s map is carefully rendered but not artistically so. The streets were drawn against a straight edge; the buildings are simple square blocks. There is no extraneous information – just the facts as he saw them.

M.M. was one of a handful of students from a rural part of O‘ahu. Of the 998 undergraduates listed in the 1931-32 register of students, only fifty-seven were from a rural or plantation town on O‘ahu (“University of Hawaii Quarterly Bulletin, 1931-32”). His community study was, therefore, unusual. However, it does share much in common with other community studies of plantation towns showing the location of the segregated workers’ camps, schools, plantation infrastructure, and small businesses.

In addition to the Portuguese, Puerto Rican, “Mixed,” and Japanese camps, there were two Filipino camps, an “old camp” near Kamehameha Highway and a “new” camp located behind the Japanese camp. The Japanese camp does not appear to be the largest; it is surrounded by the “Mixed camp” and one of the two Filipino camps. The presence of two Filipino camps reflects the growing presence of Filipino workers who began to dominate plantation labor by the 1930s. By the time M.M. created this map, Filipinos had begun to replace Japanese workers on the plantation. The Filipino population in the Territory increased from 2,361 in 1910 to 63,052 in 1930 (Andrew Lind, Hawaii’s People, p. 28).

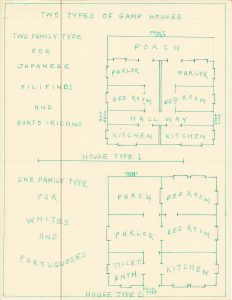

M.M.’s paper included a simple rendering of “house types” in Kahuku: the “two family” houses for Japanese, Filipino, and Puerto Rican workers and the “one family” house lived in by Portuguese and Haole residents. In addition to having a second bedroom, the single family dwellings also had indoor bathroom facilities.

The map shows two schools, Japanese and English, and three religious institutions; a Catholic church, Methodist church, and Buddhist Temple. In most plantation communities, the Buddhist Temple is near to the Japanese School and the Catholic Church is adjacent to the Portuguese, Puerto Rican, or Filipino camp. But the presence of a Methodist Church is unusual. It was founded by the first group of Korean immigrants to Hawai‘i. Fifty of the group of 102 were members of the same Methodist congregation in Inchon, Korea. Once they arrived, they quickly established chapels for services and Sunday Schools. With the help of the Hawai‘i Methodist Episcopal church, they built several Churches on O‘ahu including the one depicted on M.M.’s map. Because M.M. didn’t provide any demographic information in the paper it’s not possible to know how many Koreans were left in Kahuku at the time. However, the Church survived as the religious home of Japanese converts. By the early 1930’s, there were many Methodists and Methodist Episcopal Churches throughout the Territory and the Kahuku Methodist Episcopal church (which still exists) was one of several on the North Shore that was overseen by Japanese ministers (K. Kale Yu, “Hawaiian Connectionalism: Methodist Missionaries, Hawaii Mission and Korean Ethnic Churches,” Methodist History 50:1 October, 2011).

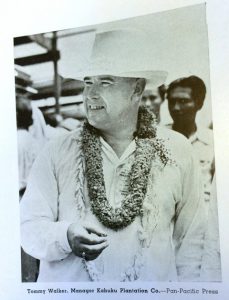

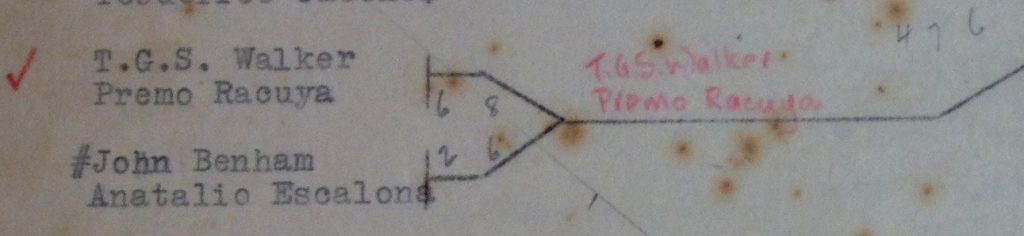

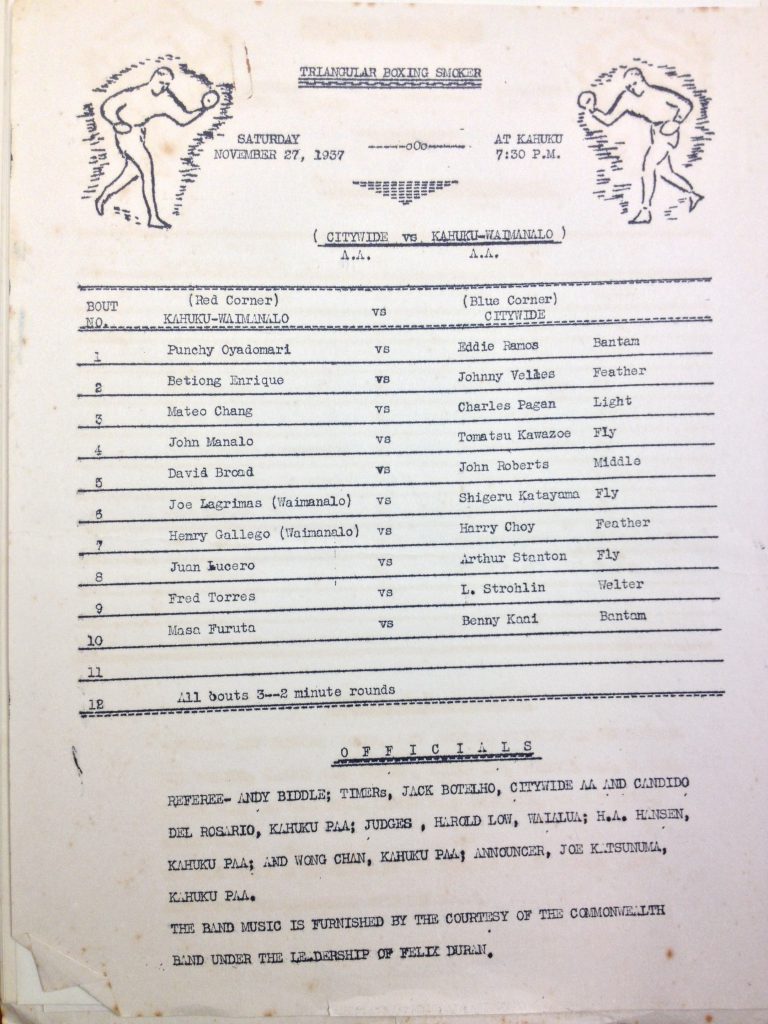

The other unusual feature of this map was an unusual feature of Kahuku – the number of sports facilities on the plantation. T.G.S. (“Tommy”) Walker who managed the plantation from 1928 to 1940 is credited with building the facilities and promoting sports competition among groups on the plantation and against other local teams. Walker earned a reputation as an iconoclastic manager; historian Lawrence Fuchs described his work as “revolutionary”(Hawaii Pono, p. 65). It wasn’t so much the use of sports as a way of quelling the pent up energy of workers but the range of sports facilities he built. At a time when tennis and golf were considered the sports of elites, Walker built facilities for both sports. He also organized tournaments in which he himself was a participant; in a 1934 Tennis tournament he and his partner, Primo Racuya advanced to the second round.

Walker and others took advantage of the enthusiasm for sports in local culture and channeled ethnic antagonisms into team rivalry. By providing recreational activities, workers – especially unmarried men – had a way to stay occupied during evenings, weekends, and holidays when they might otherwise be distracted by gambling, drinking, or illegal behavior. Kahuku Plantation was even progressive enough to host a pool room, an activity that invited gambling and fighting. But, “[t]his building is adjoined by the Police Headquarters on one side and on the back there is a training room for boxers. What a combination!”

The Paper

M.M.’s paper follows the typical arrangement for a community study. He describes the residential districts, important institutions such as churches and schools, and recreational facilities. M.M. adds to this a long description of Kahuku Hospital, the only medical facility in the area that was equipped to care for more serious injuries or illness. The hospital served “…Kaawa [sic], Kahana, Laie, Kahuku, Waimea, and Pupukea.” He also discusses the remodeling of the hospital to include new lighting, an operating room, and a waiting room. The hospital was operated by the plantation management who hired the doctor and paid to send nurses to be trained in Honolulu. In addition to treating injuries and common illnesses, M.M. reported that there were two houses on the grounds for patients with communicable diseases. This section of the paper is the only place where M.M. provides anything resembling demographic data about Kahuku: 80-90% of the patients were Filipino, 5% were Japanese, 1% Chinese, 0% Hawaiian, 5% Caucasian, and 5% Puerto Rican. The information seems superfluous, especially since he doesn’t tell us the raw numbers of patients that were seen and over what period of time. But it does show that Filipinos dominated the work force by this time, suffering the greatest number of severe injuries that required the services of a doctor or a trained nurse. (Later in the paper, M.M. describes the Filipinos working in the cane fields and the Japanese workers performing more skilled labor such as carpentry, plumbing, and masonry.)

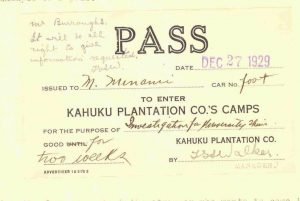

A singular feature of M.M.’s paper was the pass he received from the plantation police force that allowed him to enter the plantation camps. The pass was signed by plantation manager Walker and included a handwritten note saying that “.. it will be all right to give information requested.” M.M. would have needed to present the pass to the private police force that patrolled Kahuku. Like the hospital, the police officers were hired and paid for by the plantation. “They look after the conduct of its good people and also see that their rights are not infringed upon by outsiders or other unlawful people.”

The presence of a private police force was a reminder of the recent history of labor unrest in Kahuku. M.M., who was born in 1908, may have been too young to understand the events that led to labor strikes in 1920 and 1924 on O‘ahu. He could not have been unaffected by them; workers from Kahuku were among the first to go out on a strike that lasted six months. The dire consequences of this unrest (not the least of which was workers being thrown off the plantation and out of their homes) would have made a memorable impression on a twelve-year-old boy. M.M. makes no mention of these events, but his description of the private police force and his friendly interview with them suggests that he understood the importance the plantation placed on protecting Kahuku from “outsiders and unlawful people.”

…[T]he force can check the stranger who wants to come into the camp to pay visits to his or her friends. This pass can be obtained at the Plantation Main Office or at the Police Headquarters, by stating the purpose for entry and thereby, if he is deemed undesirable, he is cast out … otherwise the permit is granted. The undesirable classes are very similar to the undesirable immigrants (strike propagandists, cockfighters, bootleggers, burglars, prostitutes, professional and amateur gamblers, etc.).

M.M. transcribed some of his interview with at least one of the police officers. The plantation, they reported, was relatively peaceful.

Of course, there are some times cases where a man goes on a wife of another and other petty cases that are called to our attention, but aside from that, we had no particular trouble. Maybe some drinking or gambling or prostitution might be going on some time, but they are going on peacefully without any quarrel, so we cannot notice them. If things go on peacefully as here, who could stop it?

Less than a decade after the 1920 strike, the most important task the Kahuku police force performed was to prevent any further agitation through careful oversight of the workers. They turned a blind eye to petty crime but were vigilant in their monitoring of strangers. Even family and friends of plantation residents needed to obtain a pass. “If [a visitor] is deemed undesirable, he is cast out…”

M.M. did not provide any population statistics. (This information may not have been made available to him; the police conducted a yearly survey of the camp population but this information may have been too sensitive to release to the young researcher.) But based on the number of sports facilities and recreational activities, there must have been a significant population of boys and young men. M.M. describes the sports facilities – tennis and golf courses, a baseball field complete with grandstand and a boxing ring – and the tournaments and league play that kept them busy year round. M.M. expressed pride in the local baseball team calling them “matchless” and boasting about the fact that they played against a team from California. He seemed as proud of the facilities as he was of the teams:

The best baseball ground of Oahu is none other than the Kahuku ball ground. It is located on the border of the Filipino camp. The ground is very level and large. The ball was never lost in any game because of home runs. The grand stand with fairly large sitting capacity and the players’ room for dressing are also well equipped. All around the place, parking spaces for automobiles are laid out.

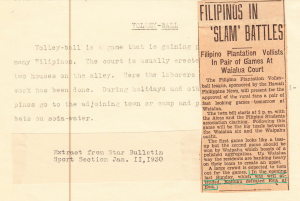

M.M. saw fit to celebrate even a less well-known sports: volleyball. Filipino workers practiced by stringing nets between their homes and played workers from other camps, in this case, beating out a team from ‘Ewa

M.M. saw fit to celebrate even a less well-known sports: volleyball. Filipino workers practiced by stringing nets between their homes and played workers from other camps, in this case, beating out a team from ‘Ewa

M.M.’s paper ends with a description of the plantation workers that reveals something about his fieldwork. He has the most to say about the Filipinos and records some of their pidgin in a conversation he had with one worker.

You like Kahuku very well?

“Me stop here six years ago; all plantations all shem.”

You go Honolulu holoholo?

“Sometime we night hanahana nomo.”

Go look friends?

“Yes, friends, gamble, hoa, all kinds.”

M.M. either didn’t interview members of his own Japanese community or they had nothing to say that he found interesting or worthy of recording in his paper. The section of the paper labeled “Portuguese” records a conversation about them, a repetition of common stereotypes. The Puerto Rican workers warrant only a sentence in which they are compared to Filipinos.

RASRL Context

M.M.’s map was the first of many finds in the RASRL collection. Although the RASRL collection contains many larger maps (some of which are showcased in this exhibit), these smaller maps, enclosed within the papers of University of Hawai‘i students had, by and large, been forgotten. These smaller maps often tell us more about the writer than they do about the community they depict. We see things from their point of view and so can only focus on what they felt was most important. M.M., who grew up near but not on the plantation, can provide only a few intimate details about the lives of the largely Filipino work force, nothing that couldn’t be seen by another casual observer. He seems more familiar with the way the community is run from the point of view of the plantation managers. We are, of course, in no position to judge his experiences. His experiences are no less valid if they go against the grain of how we now think of plantation life – a bitter struggle between workers and management, a peasant class being abused by luna and taken advantage of by the ruling elite who ran the “Big Five” corporations. In this map and paper we see the world of a young man who loved sports and was lucky enough to live in a town where they were part of the day-to-day life of the community.

The RASRL papers and maps are often genuinely surprising – a map that reveals a neighborhood that is now forgotten, fragments of slang and references to events that no longer mean much to the contemporary reader. Researchers find their families or information that wasn’t considered important enough to be saved in a repository of official documents. We hope that this material will continue to surprise new audiences for many years to come.

Mahalo to Jesse Otto for his extensive research on Kahuku Plantation.